Moulay Hassen’s real name was Oum-el-Hassen. She also used the alias Léonie Vallon. The press called her “The Ogress of Fez.” The famous French writer Collette was assigned by the newspaper Paris-Soir to cover the trial.

Moulay Hassen’s case is particularly difficult to research due

to the colorful myth surrounding her exploits. Two specific myths were

perpetuated by the press: 1) that she received the French Legion of Honor

medal, an award for which she seems to have been seriously considered for, but

which she did not in fact receive, and 2), that she was executed (by

guillotine) following her first conviction for murder in the case which

identified her as a serial killer. She was condemned to death by guillotine but

was never e executed – due to her political connections, it would seem – and

was freed allowing her to continue her career of kidnapping, torture and murder

of mostly female victims before she was again arrested, prosecuted and

convicted, receiving a sentence of 15 years in prison.

“Moulay Hassen” (Mulay Hassan) was also the name of Sultan Hassan

I (1836-1894) of Morocco. Morocco’s Crown Prince in the mid-20th century

was named Moulay Hassen, as well as the current crown prince, born in 2003.

***

***

***

FULL TEXT (Article 1 of 4): WHEN the mass-murder trial of Moulay Hassen green-eyed ex-glamor girl and night club owner, opened in Fez last month, M. Julin, prosecuting, said: –

FULL TEXT (Article 1 of 4): WHEN the mass-murder trial of Moulay Hassen green-eyed ex-glamor girl and night club owner, opened in Fez last month, M. Julin, prosecuting, said: –

“Of the fourteen girls known to have

been inmates of this club in the past year, three have disappeared, four are

dead, and seven have been tortured so badly that they will be invalids for

life.

“Once a girl entered this haunt she

was never seen again outside.”

Mohammed Ben Ali Taieb was accused as

an accomplice in the killing of Cherifa, a beautiful dancer in Hassen’s secret

club in Meknes.

M. Julin said the girls had been

starved, tortured and beaten, Cherifa had fallen seriously ill.

Fearing an injury if the girl was

taken from the house, Moulay Hassen had struck her on the head with a wooden

mallet and forced Ben Ali at pistol point to finish the murder.

She had cut up the body. Children

playing on waste ground discovered parts of it in the loose earth. The trail

led to the night club.

Search at the club revealed a

bricked-up cupboard and in it were found four girls and a boy of fifteen. They

were still alive, but all bore marks of having been tortured before they were

bound and gagged and dumped into their living tomb.

Moulay Hassen’s career was then

described to the Court. Born forty-eight years ago in Algiers, she gained fame

as the most beautiful cabaret girl in Northern Africa. When tribes from the

Atlas Mountains rebelled in 1912 and crossed the desert, she saved the lives of

twenty French officers by hiding them in her house. She was recommended for the

Legion of Honor.

After years of stardom as a dancer in

Algiers, she suddenly disappeared. She was believed to be linked with drug

traffickers and white slavers, but no trace of her was found until the police

visited the club.

Moulay Hassen was sent to gaol for 15

years and Mohammed Ben Ali Taieb for 10 years.

[“Smith Tells Of Glamor Girls’ Grim Fate in Morocco,” The

Daily News (Perth, W.A., Australia), Dec. 21, 1938, p. 6]

***

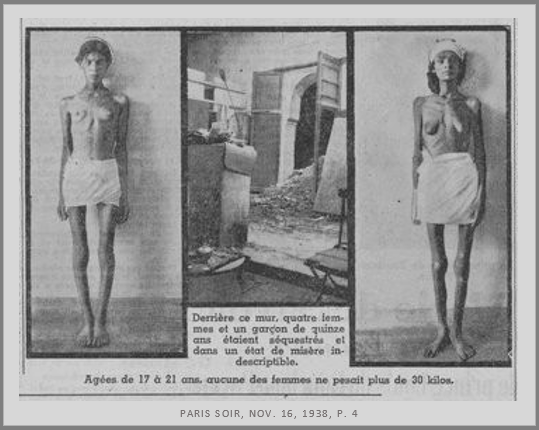

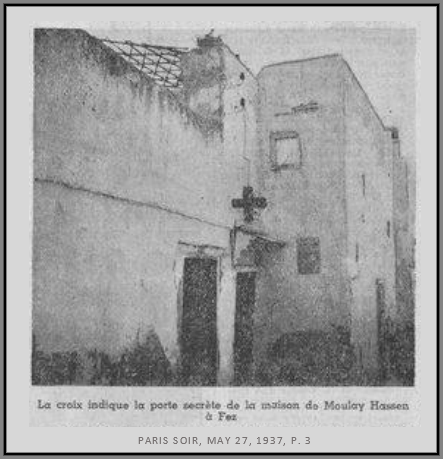

ILLUSTRATION CAPTIONS (for Article 2 of 4) - ABOVE: Developed sketch by a French police observer of the tragic moment when the wall in Mme. Moulay

Hassen’s villa of iniquity at Fez was broken into and four of her

slaves, three girls and a boy, were found starving and emaciated inside

it. --- BELOW: Cheriffa,

the Dancing Girl, for whose murder Mme. Hassen was put on trial at Fes,

Africa, where the French colonial officials condemned her and

afterwards reported her execution – but it now turns out that she did

not die at all and is still very much alive and expecting freedom.

FULL TEXT (Article 2 of 4):

~

Condemned and Officially Reported Executed for Her Unspeakably Cruel

Crimes, It Now Leaks Out That She Is Still Alive and Soon May Be

Free—But Who Her Powerful French Protectors Are and Whether They Are

Inspired by Fear or by Gratitude Remains a Dark Mystery ~

Meknes,

French Morocco. – Convicted, sentenced to death and reported to have

been beheaded in 1937, Moulay Hassen, the murderess of Meknes, turned up

the other day in a Moroccan jail, alive and kicking, with only a short

sentence to serve.

By

this unexplained dodging of the guillotine’s blade, the woman, already

the most famous as well as infamous of modern Africa, adds another

chapter to her career and joins that mysterious host of

ghosts-in-the-flesh, officially dead but supposed somehow to have

cheated the grave.

There

was the Dauphin, supposed to have survived the French Revolution, and

his counterpart, a daughter of the last Russian Czar, supposed to have

been overlooked when the Reds murdered the rest of the Royal Family.

Evidence

has been offered that John Wilkes Booth was not shot after he

assassinated Abraham Lincoln but died many years later, of natural

causes. Some believe that King Edward VI of England, far from dying in

his youth, as the histories say, became Francis Bacon, and even wrote

the works attributed to William Shakespeare. However, there have always

been grave doubts about these alleged grave-cheaters but seemingly none

at all about Madame Moulay Hassen.

Few

persons ever deserved the death penalty more thoroughly than did

Moulay, who not only murdered but tortured her victims alive. Yet the

blackness of her life was illuminated by brilliant deeds, some so

courageous as to be heroic. For one of these which was officially

recognized, she almost received the Legion of Honor, but it is believed

that others which are only whispered about, were even more important in

the eyes of the Government.

The woman can hardly be explained except as a Jekyll-Hyde character.

It

looks as if the Government of French Morocco also suffered from double

personality when it handled her case. First, as an upholder of law,

order and the sanctity of human life, it tried, convicted and sentenced

her to death for murder. Then the soft-hearted government personality

seems to have taken charge and done nothing but put the murderess in a

nice, safe cell until public opinion had cooled down. No doubt it was

mindful of what the convict had done for the Government in the past and

perhaps gave a thought to what might happen if she were put to death.

The

evidence had been so overwhelmingly against her that conviction was

inevitable, and the death sentence seemed equally so. But it was weeks

before this was confirmed in an official dispatch, followed still later

by another that sentence had been executed. When it was learned the

other day that the murderess was alive, serving a 15-year sentence from

which she may be paroled at any moment, the authorities casually

explained that the reports of the death sentence and execution were

errors.

The

one of her execution certainly was but it is by no means sure that the

death sentence was not actually pronounced and then secretly reprieved.

In any event, why did the Moroccan authorities and the parent government

at Paris make no effort to correct the errors?

It

is much as if a famous murderess were to be found alive in Sing Sing

Prison and the American authorities merely explained that reports of her

sentence and execution were errors which they had not bothered to

correct. Can it be that officialdom wanted the public to believe that

justice had been satisfied and that the truth is only now being revealed

to soften the shock of her expected release?

The

Bible relates that the woman Rahab had a house in the wall of Jericho,

in which she hid Joshua’s three spies, and for which she was duly

rewarded. Moulay also had a house in the wall of Fez, in which she saved

the lives of 16 young French officers from a mob of natives. Her house

at Meknes, from which she was taken to jail, was also in its ancient

wall. Houses in the wall had advantages which appealed to women of

Moulay’s mysterious ways.

The

French authorities had for some time heard blood-curdling stories of

tortures and even murders in Moulay’s wall-house in Meknes but, as often

as they traced them down to anyone who might really know, the man or

woman trembled and would not say anything, so they never pressed their

investigations of the woman who always replied to their questions:

“I saved the lives of 1,000 Frenchmen.”

But

one day that stock answer was not quite enough. A wind had blown down a

fig tree in Moulay’s garden and from where the roots had been children

pulled out some of the bones of what, had been a young woman. Someone

else might have placed the bones there but the police thought they would

at least make some pretense of investigating the latest rumor that four

people had been buried alive in one of the walls of Moulay’s house.

Most

of the walls gave forth hollow sounds and the young officer in charge

not knowing where to begin and remembering that he was dealing with a

woman of great political influence, decided it would be better for his

career not to begin at all. Just as they were about to leave, there came

a scratching sound.

“What is making that sound?” asked the officer, and Moulay replied without hesitation:

“It is a cat that hid in there when we had some repairs made a few days ago.”

The officer had his doubts and pounding on the wall with a pistol butt, shouted:

“This

is the police. Is anyone behind that wall? Answer in the name of the

law!” After a brief silence there came an answer, a faint mewing, like a

cat.

“Satisfied now, Monsieur Gendarme?” said Moulay, “or do you wish further to annoy the savior of General Poeymirau?”

The

officer realized that he had probably already annoyed her far too much

for his own good and with a red face bowed as a preliminary to retreat,

but he straightened up from the bow, with a snap. Another sound was now

coming from that wall, faint, hollow and ghostly, like a voice from the

tomb. It said:

“No, I will not keep quiet. Help! There are four of us here and we are dying.”

After

that the poisonous looks of the most powerful woman in Africa could not

restrain the police from breaking down the plaster and taking out three

girls and a boy, almost naked and almost skeletons.

“Water!” they moaned feebly, and it was Moulay who jumped to bring it to them, but the boy feebly pushed it away, whispering:

“No, poison—policeman get it.”

With

an angry gesture, Moulay smashed the pitcher on the floor and the

police filled another. When the four had recovered enough to talk they

told a long, pitiful story of how Moulay had enticed them into

captivity, had them trained to dance and then kept them prisoner, on

pain of death.

“We

have been in there four days without food or water,” one of the female

skeletons said. “She told us she would take us out and flay us alive if

we spoke.”

“But

I didn’t care because we were going to die anyway, if we didn’t,”

interrupted the boy. “And we can tell you whose those bones were you dug

up in the garden. They were Cheriffa—we saw her murdered and that’s why

she did this to us.”

Cheriffa

was a pretty girl somewhat older, who had been white-slaved some time

before and it was she who had told them that escape was hopeless.

Poor

Cheriffa not only had to accept the attentions of guests but stand

tortures for their amusement. One of these was to dance nude with a tray

of goblets brimming full of boiling hot tea over her head. About once

out of four times she was able to get away with the dance without

scalding herself.

On

the night of the murder, a fat old Pasha had the idea of sticking pins

half way into the dancer’s flesh and then heating them red hot with his

newest toy, a cigar lighter. He did it once too often. The tortured girl

whirled, punched his fat stomach and then kicked him in the chin so

hard she almost broke his neck. The four rescued prisoners told of how

the short-lived rebellion was put down, of seeing Cheriffa beaten to

death and her flesh fed in strips to cats.

The bones were then ordered to be boiled and buried in the garden, and after that Moulay had walled up the witnesses.

“How did the cat get in?” asked the police.

“I was the cat,” replied one of the girls.

“When

she walled us up, the old devil promised to let us out sometime if we

did not speak. But in ease anyone should ask if someone was within the

wall we were to mew like a cat. We did not see the sense of her telling

us that because we were bound and gagged. But she must have known that

perhaps one of us would get her hands loose and untie the others because

that is what happened.”

Once

the natives saw Moulay, then about 47 years old, behind the bars, the

spell of fear was broken and there was a rush of witnesses to testify

against her. The woman’s defense was not very strong except that

statement about saving 1,000 Frenchmen. This incident had happened in

Meknes when a plot to slaughter General Pocyrhirau and his garrison of

1,000 men was so carefully laid for the annual Aissaua Blood Festival

that it was not suspected and would doubtless have succeeded had not

Moulay warned them just in time.

But

it was long before that when she performed her most famous and

spectacular service, at Fez. There a regiment of native soldiers

mutinied, leaving their sixteen French officers at the mercy of the mob

Not knowing where else to go they fled to Moulay’s house on the wall for

sanctuary, and got it.

She

and her girls went to work on the young officers, making them shave

their moustaches, staining their skins, powdering their faces, rouging

their cheeks, pencilling their eyebrows, blackening their lashes,

painting their lips, fitting them into the robes and headgear of the

house’s wardrobe and dousing them with perfume. By the time the mob

broke in it found what looked like about 16 more girls than usual lying

around on the divans but no sign of the men. Off went the mob to search

elsewhere. For these and many other services, which have not been

formally cited, she was proposed for the Legion of Honor but the

respectable women of France rose in wrath against a woman of Moulay’s

profession receiving that honor. There was a delay but pressure would

probably have put the thing through had not Moulay made the tactless

remark that if they did not hurry up, she would hang the decoration on

the tail of her mule when it did come. That killed her chances forever.

Though

nobody outside high government circles can say positively it is

whispered that Moulay could tell things that must never come out. All

the more reason, one might think, for cutting off her head. But perhaps

the political dynamite is in the hands of her friends and agents, safely

in some other country, ready to be touched off unless the dangerous

woman is speedily released. At present it is just another dark mystery

of the Dark Continent.

[“Why Didn’t They Chop Off Wicked Mme. Hassen’s Head?” The American Weekly – San Antonio Light (Tx.), Dec. 25, 1938, p. 3]

***

Next morning, bathed, perfumed and for the first time in fine clothes Moulay invited them to join her band of dancers. By this time they knew who she was but thought it would be safe enough in the dance hall, from which it was always easy to escape. For a few weeks they were trained in dancing and singing, but receiving no pay, which, they understood, would only come when they were skillful enough to earn it. One evening they were delighted to hear that this tribe had arrived and eagerly followed Ali through the streets, supposedly to the house of a wealthy merchant, only to find themselves prisoners in the house on the wall.

Links to more cases: Female Serial Killers Who Like to Murder Women

***

For more Real Life Ogresses see: Ogresses: Female Serial Killers of the Children of Others

***

***

***

FULL TEXT (Article 3 of 4): Night

club orgies, which allegedly occurred in the house of a once beautiful dancer, who for years held

sway over French Morocco, gave an amazing aspect to a murder trial at Fez.

Proceedings ended in the dancer, who has been described as the ‘Female Landru of Morocco’,

being sentenced to 15 years’ hard labor, and her husband to 10 years.

Couple thus dealt with are: Moulay Hassan, otherwise “Moulay the

Nightingale” (48), owner of a night club, and Mohamed Ben Ali, her husband, who

claims to be a direct descendant of the prophet Mahomet.

The woman has had an extraordinary

career, chapters of which were listened to in court by wealthy men and women

who knew her at the height of her power.

Born in Algiers, the “Nightingale”

gain ad fame as the most beautiful cabaret girl in Northern Africa.

When tribes from the Atlas Mountains

rebelled in 1912 and crossed the desert, she saved 30 French officers by hiding

them in her house at the risk of her life.

Then she went to Maknes, where for a

second time she proved the saviour of French Army officers.

Learning that the Pasha was planning

a massacre of Europeans, following the Biff revolt, she warned the French, and

the plot was discovered.

On both occasions the “Nightingale”

was recommended for the Legion of Honor, but she never got it. During

subsequent years of stardom as a dancer in Algiers she acquired thousands of pounds worth of jewels

as the reward for performing before great Moroccan chieftains.

Little by little, however, as her

beauty faded, she lost her power and her money.

Finally she retired to a small house

in Fez where she lived a mysterious life.

She was said to be a spy, and was

believed: to be linked with drug traffickers and white slavers.

Two years ago the “Nightingale” and

her husband were arrested following the discovery of the dismembered body of a

pretty dancing girl named Cherifa.

Police investigations began when,

children playing in the street accidentally knocked over a basket and picked up

a human hand.

In the blanket were found the remains

of Cherifa.

The inquiry led to Moulay Hassan’s house, and her

husband confessed that be helped the “Nightingale” to strangle the girl.

In Mohammed’s room were found a

knife, an axe, scent and bloodstains A thorough search of the place followed,

daring which the police heard a faint tapping sound.

They found a tiny concealed room,

with no light, in which were four girls and a boy, “living skeletons,” the

heaviest weighing less than Set.

They said they had been lured to the

house by the “Nightingale,” who met them in the streets of Meknes. They were

imprisoned, beaten and starved.

They declared they had seen Moulay Hassan and Mohammed strangle

the girl Cherifa as they watched through a crack in a door.

When news of the discoveries spread

troops had to be called to prevent the angry populace from lynching the

“Nightingale”.

Wizened and bent to a degree beyond

her years, Moulay

Hassan, who was

accused of murdering Cherifa, appeared each day in the court wearing white

robes.

She listened impassively to the case

against her and her husband, who was charged as an accomplice, and to a host of

witnesses called to support it.

•◊• Girls, Starved, Tortured And

Beaten •◊•

M. Julin, who prosecuted, told the

Court: “Of 14 girls known to have been inmates of this house in a year, three

have disappeared, four are dead, and seven have been tortured so badly that

they will be invalids for life. “Once a girl entered this haunt she was never

seen again out side.”

M. Julin declared the girls, of whom

Cherifa was one, had been starved, tortured, and beaten. When Cherifa fell ill,

Moulay Hassan

struck her on the head with a wooden mallet and forced Ben Ali at pistol point

to finish the murder.

Moulay Hassan denied the charges, and I said the girls were her tenants,

whom he saw only once a week when they paid the rent. Ben Ali, she alleged,

killed Cherifa. Asked to explain the discovery of the boy and four girls in the

secret room, she said: “I know nothing about it.”

Ben Ali denied his wife’s story, and

said he was only an unwilling accomplice forced to murder Cherifa under a

threat that the “Nightingale” would shoot him.

Asked if the girls or anyone else

knew of the crime, he replied: “No one but Allah saw us.”

Addressing Ben Ali, the judge said

“You are a descendant of the Prophet by the Smailia branch, but you were not

presented from abandoning yourself at an

early age to the basest debauchery.”

[“’Female Landru’ Of Morocco -

Beautiful Dancer Denies Throttling Dancing Girl” The Mirror (Perth, W.A.,

Australia), Dec. 17, 1938, p. 8]

***

FULL

TEXT (Article 4 of 4):

“Then

she let them down by a cord through the window; for her house was upon the town

wall, and she dwelt upon the town wall.” — Joshua II. 15.

MEKNES,

French Morocco. – MOULAY HASSEN for many of her 47 years ran a more or less

exclusive but hospitable harem on the wall of Meknes, exactly as did Rahab on

the wall of Jericho, when she saved the three spies of Joshua, according to the

Old Testament narrative. This modern Rahab prospered even more than the

Biblical one, but the other day she was thrown into prison, charged with a

series of crimes, including walling up alive three girls and one boy and

chopping up the body of a rebellious bayadere [temple dancer], spicing the

pieces with catnip and feeding them to her pampered pack of pet cats.

Yet,

in 1912, all France hailed this woman “whose house was on the walls” as a

heroine because she had saved not three men, as Rahab did, but sixteen French

officers, in her den of vice by disguising them as some of her girls. In 1925

France rang with her praises again for betraying a great conspiracy against

General Foeymirau’s troops at Meknes. For this she was proposed for the Legion

of Honor and almost, but not quite, received it.

For

many years this wall-girt city has been full of whispers about Moulay Hassen,

once beautiful but now with a face as hard as the jewels which weigh her down.

They were tales of murders and torture so fantastic, that when they reached the

ears of the French ruling class, they caused only amused smiles. No modern

woman could be such a devil, they thought.

The

natives believed, but never complained to the authorities because they were

mire she would not be punished and they feared her vengeance. They saw the

highest army officers and government officials bow low, as if she were royalty.

Lest there he any doubt of her influence, the woman used to boast:

“The

French owe me a thousand lives and I have not yet collected all the debt.”

Like

Kipling’s Lahm, in his famous story, “On the City Wall,” she could leave her

great fortune in jewelry lying about unguarded and nobody dared rob her. Yet

this idea that she was above the law was entirely a delusion which was

shattered by the innocent hands of a couple of little children.

Moulay,

besides her original house on the wall, had acquired a dance hall and a private

home with a large garden in the native quarter. Into that garden one day two

small boys managed to penetrate and amused themselves by digging a hole in the

soft earth under a fig tree. After a while they wandered out into the street

carrying with them some queer white things they had unearthed. A few minutes

later a police inspector found them trying to fit together the bones of a human

hand. Investigation brought to light the almost complete skeleton of a young

woman scattered about the earth under that fig tree.

To

the astonishment of the natives, the police confronted Moulay in her house on

the wall

for questioning. Haughtily the woman who had almost won the Legion of Honor

denied knowledge of the bones and reminded them that they had better remember

to whom they were talking. The questioning inspector finally paused and was

remembering that very thing when he heard a faint scratching sound behind a

recently-plastered wall.

“What

is making that sound?” the inspector asked.

“A

cat,” replied the woman. “I have many here, as you can see, and one must have

gotten imprisoned last week when workmen repaired the wall.”

“Let

it out,” the inspector ordered, and the woman answered:

“I

have already arranged for a plasterer to come tomorrow. He will know how to

make a small hole and not do much damage.”

The

inspector looked searchingly at Moulay’s hard face, which pave no indication

that she was not telling the truth. But his eye wandered to Mohammed Ben Ali,

one of her servants, who was trembling.

“Ali,”

he snapped, “by Allah, tell the truth —what’s behind that wall?”

Ali

wrung his hands, but he answered:

“Allah

is my witness it is only a cat.”

“We

will see,” said the inspector, drawing his pistol and with the butt striking

three blows. The wall gave back three hollow sounds. He cried:

“This

is the police. Is anyone behind that wall? Answer in the name of the law.”

There

was a tense silence, and then, from behind the wall, came a faint mewing sound,

like a cat. Monlay Hassen smiled.

“Satisfied

now, Monsieur Gendarme?” she asked. The inspector’s face turned red as he

realized that, perhaps he had gone too far with the “savior of Gen. Poeymiran.”

Then came a muffled voice speaking through the wall. It said:

“No, I will not keep quiet. Help! There are

four of us here and we are dying.”

The

police went to work on the wall with he nearest tools they could find, and soon

dragged forth three girls and a boy, almost naked, hardly better than skeletons

and more dead than alive, from a space so narrow that they had no room to lie

down.

They

were given water, and then the police wanted to know why they had mewed like a cat

instead of calling for help the first time. One of the girls spoke faintly, as

she rolled sunken eyes at the Hassen woman:

“She

ordered us to make a noise like a eat if anyone should knock on the wall. She

promised, if we did, to let us out before we died, but if we spoke she would

torture us to death.”

“But

I did not believe her, so I cried out to you,” the boy skeleton interrupted. “We

have been here four days without food or water, but we know whose bones those

are you bringing up in her garden. That was Cheriffa, the dancer.

“We

saw her murdered.”

“What

have you to say to this?” asked the inspector sternly. Scornfully Moulay is

reported to have answered:

“France

owes me 1,000 lives.”

Whispers

fly fast in Meknes, and when the ambulance arrived for the four half-dead

victims, a great crowd had massed beside the wall. With only a murmur, the

natives watched the four taken away, but when the police appeared with Moulay

Hassen a prisoner, a roar went up and the police had all they could do to save

her from being torn to pieces.

As it

was, the mob did pretty well in the way of souvenirs, because Moulay had

insisted on going to jail as she went everywhere, loaded with jewels, moat of

which disappeared in the scuffle. Already gems are being offered to tourists,

guaranteed “by the beard of the Prophet” to have been snatched from the throat

of “Moulay Hassen.”

After

twenty-four hours in the hospital, the four prisoners in the wall gave such

testimony that Ali broke down and corroborated it. Now that, the police say,

the spell of terror this woman had yielded was broken, many other witnesses

came forward, so that the authorities assert that they have a complete case

against Moulay for the murder of Cheriffa, but they are trying to find out what

became of ten other girls who disappeared in that house on the wall.

The

four prisoners in the wall said that they had once been a little band who

danced and sang to pick up pennies in the foreign quarter until one night a

woman, covered with jewels, asked them how they would enjoy eating all the good

food they could. Though they did not like the woman’s face, the four were

children of the native poor who had never seen a square meal, except through a

restaurant window, and the appeal was irresistible. She led them to her dance

hall, where she fed them till they fell asleep in their chairs.

Next morning, bathed, perfumed and for the first time in fine clothes Moulay invited them to join her band of dancers. By this time they knew who she was but thought it would be safe enough in the dance hall, from which it was always easy to escape. For a few weeks they were trained in dancing and singing, but receiving no pay, which, they understood, would only come when they were skillful enough to earn it. One evening they were delighted to hear that this tribe had arrived and eagerly followed Ali through the streets, supposedly to the house of a wealthy merchant, only to find themselves prisoners in the house on the wall.

There

Moulay, with the satisfaction of .a person who has played a practical joke,

explained that they were slaves for life, and death would be the punishment for

any attempt to escape. At first they could not believe it and turned to

Cheriffa,” a beautiful young dancer, who looked at them with sad, sympathetic

eyes. Cheriffa showed them the scars on her own back and told, them hopelessly

that Moulay was above the law, all powerful, and that there was nothing to do

but submit to their fate or die. This was their story.

The

girls had to receive the attentions of Moulay’s paying guests and the boy was

kicked about and beaten as if he were a pariah dog of the streets. Occasionally

the four protested, always being answered with the lash on their naked backs.

One of the brutalities which especially delighted the cruel guests of the house

was Moulay’s own invention, “the hot tea dance.”

In

this the dancer appeared nude but balancing on her head a copper tray, loaded

with brimming tumblers of boiling hot mint tea. With this burden the dancer was

forced to go through

a series of acrobatic movements which, with great skill and luck, might be accomplished

without spilling the tea. The expert Cheriffa was able to do it about once out

of every four times, on the others she scalded herself to the vicious delight

of Moulay’s especial customers.

Cheriffa,

with the fatalism of the Moslem, endured her sufferings without a moan, but one

night the worm turned. The guest of honor on this occasion, was a powerful old

tribal chief,

who with Moulay, had taken heavily of hasheesh, a drug that often inspires the

most fiendish cruelty. After Cheriffa had been scalded twice with hot tea, the

chief insisted on sticking pins into her back and then heating them red-hot

with his newest toy, a cigar lighter.

But

the chief heated up one pin too many. Suddenly the dancer whirled, punched him

in his

fat stomach, and then as he started to collapse, delivered such a powerful kick

on the point of his bearded chin that it almost broke his neck. Hoping that she

had killed him Cheriffa turned on Moulay with such a torrent of invective as

made even that hardened creature wince. The three girls and the boy said they

followed their leader in her brief and hopeless rebellion. With the aid of the

guests, Ali and other servants, the mutinous five were quickly bound and

gagged.

After

the chief had been taken away still unconscious, Moulay attended to the matter of

punishment. While waiting for masons to arrive, she gave each of the four an

unmerciful beating and then had them walled up with those instructions about

mewing like a cat in case anyone asked who was behind their wall. Since they

were gagged as well as bound, this seemed needless advice, but Moulay had

experience in such things and evidently foresaw the possibility that one might

untie his hands and release the others, as indeed happened very shortly.

They

dared not try to break out at first, but contented themselves with scratching

with a stick enough of the still-soft mortar to make a peephole from their

prison. It was through this chink the prisoners say they saw Cheriffa first

beaten to death and then her flesh cut into thin strips to be fed to the cats.

When, for some reason the animals at first refused to eat human flesh, they say

that Moulay spiced it with various herbs, including catnip, after which the

cats accepted it. When this was over, they state that they heard her giving

orders to boil the bones and bury them in her garden.

Ali

revealed the alleged fate of Aicha, a dancer before Cheriffa, who had lost her

health and looks under the abuse until she was no longer of interest to the

guests of the house on the wall. Accordingly Aicha was notified that Ali was to

take her to another house, in Rabat. The broken-hearted girl agreed, because

nothing could be worse than what she was enduring. Just before their departure

Moulay handed Ali, he says, a little loaf of bread, full of strychnine,

whispering:

“When

you get to Kenisset, get off the train, take Aicha for a stroll in the

outskirts of the town, make her eat this loaf and then leave her.”

The

servant followed instructions, returning to Meknes alone, after leaving the

dancer dying

under a tree. After describing the girl’s convulsions, to his mistress, she

expressed herself as satisfied, he said. Asked what he had been paid for

murdering Aicha, Ali replied:

“Nothing

at all except that she did not kill me as she would have done had I disobeyed.”

Ali,

who is forty-six years old, was well chosen as a slave of terror. But once that terror’s grip was broken, he

proved a bad investment for Moulay by the stories he told.

Born

somewhere in Algeria, Moulay Hassen must have been the runaway black sheep of a

decent family. This was evident at the height of her fame and power, because

not so much as a distant cousin even claimed relationship, and she never told

who she really was. Yet to have been a relative of this influential person

would have meant much profit in the way of graft and easy money. Her present

downfall proves the wisdom of this silence.

At

the age of eleven, a pretty, overgrown child, precocious in every way, she

first appears as a follower of the French armies in Africa, and already

something of a dancer. At twenty-one she had become an accomplished dancer and

was already a business woman in a rather a big way for the country and the

times, hiring other girls to work for her and beginning to get rich.

Always

alert for new opportunities, she and her corps of girls followed the Moynier

column into Fez, in 1911, and by the following year was running the largest

“institution” of its kind in the city.

Then

she met a wealthy captain who fell in love with her. He offered to buy out her

“establishment” in Fez if she would come to France with him to spend his leave.

For a large sum of money she consented. She became a favorite in Paris and made

many friends, especially in military circles. But she soon tired of the young

captain and passed from one admirer to another, collecting costly presents,

mostly jewels, on the way.

Following

the Agadir incident, in 1911, which resulted in the over-throw of the Sultan of

Morocco, a French protectorate was established in Morocco. Moulay saw in this

an opportunity to make money and returned. In Paris she had met many of the

officers who now staffed the army of occupation. She received special

considerations from them and organized a troupe of dancing girls to provide for

the soldier’s amusement.

She

divided her “employes” into three divisions. The first was made up of native

girls and

was reserved for privates in the regiments. These girls followed the various

divisions on their long marches and often went into the desert to dance at the

lonely garrisons. The next class were white women, some of them of education

and excellent family, most of them victims of the still flourishing while slave

trade on the African coast. These women had a house of their own and

entertained officers for the most part or officials stationed at permanent

posts. The final class of women entertainers were the dancers who were coached

and trained not only to dance seductively but to play love songs on the

“gombri,” a kind of mandolin that is supposed to stir the blood of those who

listen to it. These women lived in a luxurious house in Fez to which only the

wealthiest officers of the garrison were invited.

Noted

cooks were imported to concoct new dishes for the jaded palates of the

soldiers. Moulay eagerly searched for new talent to entertain her guests, and

although she often treated the girls who worked for her with savage cruelty,

she went out of her way to be kind and generous to those who naked for help.

She did this to build up a good reputation for herself with the townspeople of

Fez and to keep her house in good standing with the military authorities and

the police.

One

day a fortune-teller who professed to read the future in the sands of the

desert told her:

“Once

in every woman’s life pity takes the place of duty. You have come to me more than

once for help and I am going to give you a good piece of advice. The French are

your friends here in Fez. Tonight the lives of several officers will be menaced

by a mob. It will be in your hands to save them. Only under your roof will they

find protection. Pity them, forget your duty to your fellow-countrymen, and you

will never regret it.”

Moulay

went away undecided about warning the commandant at the garrison. Finally, she

did go to a Lieutenant Garnler and told him of her fears. The officer laughed

at her but decided to have a little relaxation with his fellow officers at

Moulay’s expense and accepted her invitation to spend the night under her roof.

At

that time Fez was peaceful and an insurrection of Moors against French rule had

supposedly been crushed. The officers at the garrison took advantage of the

lull and set about to enjoy themselves. The rebel leaders were waiting for just

such a chance to take the officers off their guard.

That

night as Moulay Hassen gaily filled the cups for her friends an angry mob

gathered in the city and stalked the streets looking for men in uniform.

Someone whispered to the leaders of the mob that several French officers had

been seen entering Moulay’s “house on the city wall.” The rebels rushed to the

home and began storming it, for it was built like a citadel.

As to

what happened thereafter, there are two versions. One, the less credible

perhaps, is that Moulay told the officers to follow her, and she hid them in a

room at the back of the house.

By

this time the mob had forced the door and the leaders went in search of Moulay

whom many of them knew well.

“Moulay

Hassen,” one of the leaders said, “we know that you have hidden some French

officers here. We have come for them.”

As he

finished speaking Moulay drew a pistol from under her robe and shot him. The

rest of the mob drew back and Moulay moved to the door which covered the hiding

officers, spread her arms across it and said:

“You,

Mohammed, whose son lives now because of the remedies I gave him as he was

dying, and you, Tahar, whom I saved from the executioner’s axe, were you ever

ill-met at my doors? Did I ever refuse you the welcome of my house and the

bread from my cupboards? You, Selim, Mansour and said, have you ever knocked at

my door in vain, when you were cold or hungry or thirsty? Tonight I would be a

dog to let you interfere with my guests, whoever they may he. You would be dogs

to violate the sacred laws of Mohammedan hospitality.

“If

you are dogs then enter, pass over my dead body and murder my guests and may

the anger of Allah and the Prophet be upon your heads and on the heads of all

your descendants, forever.”

The

mob listened, were ashamed, and went away.

The

other version of the story which is more generally believed but which is not

quite so

flattering to the French officers is that Lieutenant Gamier and fifteen other

French officers,

fleeing for their lives from the angry mob, found themselves in front of

Moulay’s door and begged her to hide them.

“Impossible!”

the young woman told the breathless young men. “They will hatter down that

flimsy door and search the place. No, wait. There is only one way. Do as I tell

you, quick”

‘Herding

the fugitives into one of her back rooms, she first had them shave off their

spiffy little moustaches and beards and then made them take off all their

clothes. With the other girls as assistants, she stained their white European

skins the tawny color of the native women, put wigs on some, turbans on others,

pencilled their eyebrows, painted, rouged and powdered their faces, drenched

them with perfume, covered them with jewels, and dressed them in the most

elaborate garments of the house’s wardrobe, forcing the real girls partly to

undress.

Distributed

gracefully on couches together with the genuine girls, the disguised officers

were impossible to detect from the real thing, in the dim light of closed

shutters and much cigarette smoke. From the entrance, the scene looked like a

Sultan’s harem. There was a furious pounding at the door but Moulay took one

last look and gave a last warning:

“For

the Jove of Aliah! Get your big feet out of sight.”

Pistol

in hand, she then opened the door. Half a dozen leaders of the mob pushed in

but hesitated at her levelled pistol.

“We

want to search your place for Frenchmen,” they announced, and were quickly told

that there were no men in the house.

“We

are told that they were seen going in. Anyway, we are going, to search,” they

said.

“It

is a lie,” cried Moulay, with flashing eyes. “If you are honest, you may

search. But if it is only a pretext to molest my girls, I will shoot through

the heart the first man that attempts it. Voila! There they are. You may

look—hut must not touch.”

A

wise precaution for the Frenchmen.

Tile

leaders gazed upon what to them was a most alluring spectacle and hesitated

again. The charming girls nearest to them were voluptuously feminine and

scarcely clothed at all.

Those

further back were more modestly clothed but so shy that many of them peeped

coyly at them with only one eye over the top of a cushion.

This

was a time of pillage and riot. Why should these expensive plums, ordinarily

beyond their reach, escape their clutches?

Moulay

read their thoughts and her voice was caressing as she suggested:

“Come

back tomorrow, after it is all over.”

That

settled it. The leaders made a search of

the other rooms, found nobody, and on their way out paused once more to feast

their eyes on that harem scene.

Just

as the others were turning toward the door, one of the six evidently recognized

one of the disguised sixteen. With a shout and outstretched arms, he started

into the room.

The

shout died on his lips as Moulay shot him through the heart.

The

other five turned around, their hands going to their weapons, in sudden wrath.

Moulay’s voice was deadly as she spoke:

“I

warned him I would do this. Who wants to die next?”

Then

her voice fell again to that caressing tone as she looked significantly at the

leader.

“Can’t

you wait till tomorrow?”

“Yes,

if you will remember me,” the man agreed.

“And

me – and me – and me,” jealously cried the others as they went out, hardly

looking at the dead man they were carrying.

Next

day the surviving five were not disappointed, because Moulay lived up to her

reputation of “the little liar who keeps her word.” Though sixteen of her

“houris” were absent from this party they were not missed.

For

heroic, quick thinking Moulay’s achievement would be hard to beat, even if she

was saving foreigners from her own people. The officers presented their rescuer

with a bronze statue of herself which nobody recognized because the sculptor

felt, it his duty to give her a Joan-of-Arc expression which was an even better

disguise than she had given the young officers. They also handed Moulay a purse

of 1,100 francs and politically she became the “Queen of Fez.” Her “salon,” as

she liked to call it, was frequented by men in gold epaulettes, who

explained when this was noted, that the Hassen woman had become a valuable

“intelligence department.”

This

proved literally true in 1925 when she performed another service to the French

arms, not so dramatic but more important because it was estimated to have saved

about 1,000 lives.

There

she wheedled from a native the details of a plot by a local Pasha to massacre

Gen. Poeymiran’s garrison during the annual Aissua Blond Festival. On this

occasion 100,000 religious fanatics would he ill town and the Pasha’s followers

planned to incite this horde to join them in attacking the French soldiers.

Moulay informed the general in time for him to place the Pasha and his

lieutenants under arrest and the Blood Festival went off without bloodshed.

This

time France almost went into hysterics of adulation over the woman who someone

said was worth more than an army corps. The climax came when someone proposed

her for the Legion of Honor, and for a while it looked as if she would receive

it.

This

was a little too much for the respectable women of France to stomach. Protests

poured in and wives of men who held that honor said their husbands would throw

it away if it was bestowed on a woman of such dishonorable profession. Yet it

might have gone through had not Moulay, herself, piqued at the delay, announced

that if they did not hurry up she would, like the Chief of the Haehem Tribe

when he received it, tie it to her mule’s tail.

That

statement killed her chances, and, though she pretended to scorn the

decoration, covering herself with a fortune in gems, it really, broke her heart

because it permitted respectable women to snub her.

She

turned to hasheesh, which the authorities say is enough to explain the rest of

her behavior.

[“Wicked Madame Moulay Hasssen and her ‘House on the City

Wall’ – Like Rahab Who Saved the Spies of Hoshua, She Saved the Lives of

Sixteen French Officers by Disguising Them as Her Girls, but When She Was

Charged With Making Her Beauties Into Food for Her Beauties Into Food for Her

Pampered Cats and Walling Them Up Alive, Her Distinguished Protectors Forgot

Their Gratitude,” American Weekly (San Antonio Light, Tx.), Sep. 12, 1937, p.

4]

***

***

Mohammed Ali, Moulay Hassen’s henchman – “Cherifa,” he said

referring to the girl whose decapitated head so staggered Yussef Bey, “refused

to obey Madame, so after lacerating her, we put a cord around her neck, and

ordering me to pull one end while she pulled the other, we slowly garroted

her.”

This damning testimony was confirmed by the five skeleton-like prisoners, three of whom since died. For Cherifa’s expiring agonies were enacted before them.

This damning testimony was confirmed by the five skeleton-like prisoners, three of whom since died. For Cherifa’s expiring agonies were enacted before them.

It was this sadistic-minded woman’s diabolical joy to abduct

attractive young girls, several of European nationality, and use them in staging

fantastic, indescribable orgies for the entertainment of her depraved guests.

Those who resisted, she shacked in her fetid, verminous

dungeons to be whipped, tattooed with hot irons, and bastinadoed at leisure.

Finally, if they still remained defiant, they were dismembered and smuggled out

of the city for burial in the sands.

It says much for the courage of Moulay Hassan’s girl victims

that 100 of them at least, according to authenticated evidence, chose death

even this awful form rather then yield to her demands.

[Stephen House, “Mass Murderess Once Won the Legion of

Honor,” The Star (Wilmington, De.), Oct. 3, 1937, p. 10] (this article reports

the erroneous story of Hassen’s execution and the false story of the Legion of

Honor)

***

***

***

Links to more cases: Female Serial Killers Who Like to Murder Women

***

For more Real Life Ogresses see: Ogresses: Female Serial Killers of the Children of Others

***

***

[11,278-1/13/21; 17,290-5/14/23]

***

No comments:

Post a Comment