4 – That in May last Mr. and Mrs. Perkins were jointly the recipients of a series of letters threatening death two being signed “A. M.,” the initials of Miss Abbie Mitchell, a friend of Mrs. Perkins, who, however, has denied al knowledge of these letters and has submitted specimens of her handwriting for comparison with the handwriting hand in the anonymous communications. Miss Mitchell has been fully exonerated.

5 – That the poison had been administered by a woman.

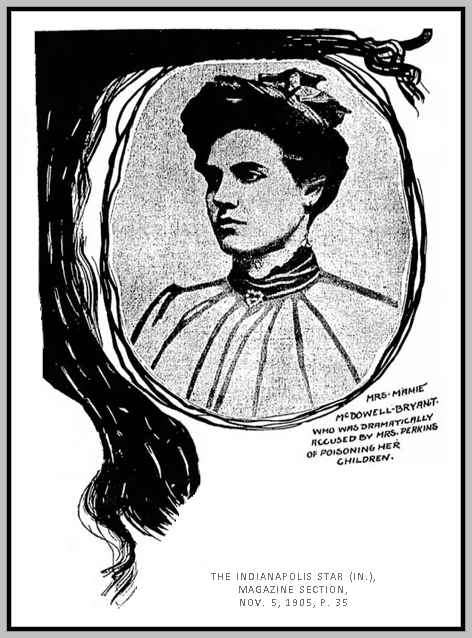

6 – That both children had been nursed I by Mrs. Mamie

McDowell immediately before their deaths.

The rest of the evidence given at the inquest powerful in its effect upon the general public sentiment, is after all so much conjecture and expression of opinion unsupported by other evidence.

The embodiment of vengeance personified does Mrs. Perkins grimly relentless, arise from her seat on the witness stand and pointing to the placid figure of Mrs. Mamie McDowell, cry out: “You ask me who I believe to be the murderess of my children. My answer is: There, before you, smiling at me from that doorway, Mamie McDowell, the woman whom I knew as Mrs. Bryan. Mamie McDowell wrote those letters and children with phosphorus obtained from matches.”

But, asked to define an adequate motive for the murder on the part of Mrs. McDowell, Mrs. Perkins grows confused and cloudy and weak, helplessly falling back at last upon a reiteration of her accusations.

Following is Edward Perkins, a mild, wispy, timid little man, quietly suggesting

his own acquiescence in his wife’s belief that Mrs. McDowell killed his

children, the stern, indomitable figure of his wife confronting him as he gives

his testimony.

More startling than all and yet absolutely worthless and

inconclusive in the hands of a skillful cross-examiner was as the “expert”

expression of belief on the part of the local post office inspector, John

Bulla, that four of the many anonymous and threatening letters received by Mr.

and Mrs. Perkins during the period per covered by the deaths of the two

children were written by Mrs. Mamie McDowell.

The local authorities in an inspiration of imitation had recalled a certain incident in the Molineux case and had requested that Mrs. McDowell give them a specimen of her handwriting. And so on a postal card the woman smilingly acquiescent, had written at dictation.

~ Compared the Writing. ~

The inspector then, for the of the jury explained that in comparing an admitted with an anonymous handwriting the expert judged by general characteristics. Several characteristic peculiarities in the handwriting of Mrs. McDowell, he said, had been repeated in anonymous letters, and on “general characteristics” he had no hesitation in expressing the belief that Mrs. McDowell was the authoress of all the letters.

No sign of fear or trepidation, no sense of the hundreds of eyes turned upon

her, some already condemning; some filled with scorn and abhorrence, was to be

seen in the trim little figure of the woman who arose at the demand that she he

should tender an explanation.

And in fluent, easy phrasing, smiling at the coroner, the jury, doctors, the police officials she gave her reply as, asking with her candid look of a child, what had she to explain. She had loved the two children. They had been often to her home. She had given a cake to Octavia on the day that the little one was taken ill. But sure the child had complained of sickness all the previous day. Why would she, a widow with three little children (here Mrs. McDowell put her handkerchief to her eyes), seek to harm the children of another woman? How could write these cruel letters? She knew nothing of poisons. Well, yes; she did remember, come to think of it, that Mrs. Perkins had called her into the house one day shortly before the illness little Willie and asked her to help in poisoning the dog, and that she had held the dogs head while Mrs. Perkins poured stuff down the dogs throat. And the stuff smelt like garlic. This, however, might be merely a coincidence.

So, Mrs. Mrs. McDowell, or Bryant, ran the course of her narrative until, with a smile and a nod to the jury, she tripped out of court.

And in face of this situation there is no cause for surprise that the Richmond

coroner’s jury took refuge in the time-honored “Murder by poison administered

by some person or persons unknown.”

But behind the curtain that shields the murderess lies the story of a deep unfathomable well of passion running through the dull lives of these of these simple, commonplace country people, whose only hope in this this world is to earn bread, and work until they die; a story of baffled love turned to hate; of a woman transformed to a fury by the indifference of the man she sought, and striking at the heart of the mother, who she hated, through her innocent children.

“Woman’s worst and coldest crimes are committed for the sake of love those of

men for money,” says Lombroso.

And eloquent on its testimony of the working of a woman’s heart under the stress of passion is the first of the line of letters dropping one by one into the home. The first letter bore a border of black and is among those not yet given out for publication.

~ The Border of Black. ~

“The border of black is for my first my first love,” said

the writer. “You robbed me of the man I wanted – he who is now in his grave.

And now I am determined to strike at you. It is my purpose first to break your

heart by making you childless, and the then to free your husband. That it is my

purpose to do this you may know.”

The mother smiled and put the letter aside. A week went by and there came another letter.

“You have taken no heed of my warning,” said the writer. “I tell you I’ll strike through those you love most.”

And with each morning there lay on the breakfast table, in sinister significance, the letter with the handwriting that they knew so well.

Heavier and heavier grew the hearts of the parents with each of those letters.

But at last there came cam a morning when the familiar step of the postman passed by their door. A second and a third morning came and went with still no letter.

And they cried for Joy at the thought that the shadow of

death had been be n lifted from them. The mere incident of the house dog dying

in convulsions was not sufficient to attract attention.

Never was the thought the unknown avenger less present to their minds than on that September afternoon when the baby Willie toddled out to the doorway and then a few yards along the road.

Only half an hour had passed when there appeared in the doorway a man bearing

the motionless figure of the child in his arms.

He had been found lying in the roadway near his father’s cottage.

No one at that time took any particular notice of the odor of garlic on the breath of the child.

At that the doctors could say was that the symptoms indicated the presence of some foreign substance in the body. Within twelve hours the boy was dead.

~ The Poisoning of Octavia. ~

The heart of the mother was full of a foreboding of that which was yet to come.

With the coming of Monday morning there again lay the

familiar envelope on the table.

“There is reason in this warning?” wrote the sender of the

letter. “There will be more reason before I am done with you.”

And now the letters came with every post; slander was now

alternated with commonplace verbiage, and these letters, really telling little

of the hideous truth, are the only communications made public by the police at

the inquest.

Then once more came a cessation of the letters, and the

parents, trembling, waited.

All through these weeks had Mrs. Perkins, quietly watching, bent her eyes on the one woman who of all others, by reason of old memories of which she even now will not speak, she believed hated her.

“There is a woman who is killing my children and who may take my husband, as she would have taken the other,” she said.

The world now knows the story of the October afternoon on which the child Octavia was to meet her death by the hand of the poisoner.

She had risen from her mother’s side, and run lightly to the

house of Mrs. McDowell, and the next that was seen of her was when she

reappeared in the doorway of the Perkins cottage, and with a sigh and a moan

fainted in her mother’s arms.

Again was the characteristic odor of garlic; again the shivering convulsions and the sharp gasps and cries of agony, ere eight hours later death released the sufferer.

Suspicion had in the mind of Mrs. Perkins become certainty. From that that

moment the word “murder” took the place of all others in the vocabulary of the

Richmond people. Mrs. Perkins spoke at last and cried out for vengeance on the

woman who, she declares, killed her children and would have robbed her of her

husband.

Two women confront each other over the grave of the murdered

children.

Mrs. Perkins, defiant, accusatory, pointing with uplifted hand at her supposed enemy. Mrs. McDowell, smiling, suave, perfect in poise, parrying each thrust, denying all things, and laughing at her accuser. Justice, in the persons of the police and the coroner, looks on the picture in perplexity and doubt, while all Richmond awaits the next development in the play.

[“Slaughter of the Innocents Chills Richmond’s Heart.” The

Washington Times, Magazine Section, Nov. 5, 1905, p. 3]

***

***

***

***

***

***

***

***

***

***

***

***

***

***

[615-5/9/22; 1860-7/17/22]

***

No comments:

Post a Comment