Deaths:

Emil Marek, died July 1932

Mrs. Kittenberger, boarder

Susanna Lowenstein, aunt

Ingeborg Marek, 3 (in some sources, 7 in others), daughter

Daughter, 9 mo., died Aug. 1932 (not mentioned in murder

counts)

***

FULL TEXT: When Inspector Rudolph Peternell, one of the youngest detectives on the Vienna police force, entered the house on the Kuppelwiesergasse that morning of Oct. 31,1936, he certainly had no reason to suspect that he was ringing up the curtain on one of the most astounding spectacles of crime in history.

He

had come in response to a phone call from the tenant of the pretentious

apartment, Mrs. Martha Marek. Mrs. Marek, long a widow, had reported that her

place had been robbed of valuable tapestries and paintings during the night.

The

comely, titian-haired woman had apparently suffered a paralytic stroke – quite

recently, as Inspector Peternell was to recall – for she limped, and her left

hand dangled lifeless. Moreover, she appeared to be sightless.

In

answer to Peternell’s routine questions, she stated that on the previous

evening she had sent her maid to a movie and retired early. The maid had not reported anything unusual.

“In

the morning, however, on entering the drawing room, I soon discovered that

certain articles were missing,” said Mrs. Marek. “Not only tapestries and

paintings, but jewelry.” The inspector inquired:

“You

heard no suspicious sounds during the night?”

“No,”

she replied. “Ever since suffering a stroke, I have been a very heavy sleeper.”

“Can

you give me an estimate of your loss, Mrs. Marek?”

“I

have been thinking about that. I should say between $2,200 and $2,800.”

“Are

you insured against theft?”

“Fortunately,

yes. I have a policy covering my house against the dangers of fire and theft in

the amount of $2,200.”

The

detective made a list of the missing valuables, then took his leave. On the way

back

to

headquarters, he recalled reading in a news paper that Mrs. Marek had been in a

gay night club. There had been nothing in the item to indicate that she wasn’t

enjoying excellent health.

Also,

the officer wondered why house-breakers would haul away heavy tapestries and

paintings and pass up numerous less bulky articles, such as silverware.

***

PETERNELL’S

superiors listened to his report, perused their records, and then decided to

institute a secret investigation.

Their

records relating to Martha Marek were voluminous and extraordinary.

She

had come into the world some 38 years previously in the town of Sopron,

Hungary. Her father had never been identified.

Soon

after her birth the infant was placed in the care of a chef and his wife; later

her mother, married Rudolph Lowenstein, stationmaster at Baden, near Vienna.

When

Martha was seven, her stepfather left Austria for the United States and was not

heard of again, at least by his family.

Martha

next received shelter and education in a charitable institution in Vienna.

She went back to her mother at the age of 12 and became an

errand girl for a dress shop.

Then

in 1911, when she was 13, she made an acquaintance which was to have a very

important effect on her future.

She

met Moritz Fritsch, proprietor of a department store in downtown Vienna.

Fritsch,

who was 62 but looked and acted at least a decade younger, observed her on a

street car, noticed she was thinly clad and apparently undernourished.

He

engaged her in casual conversation, learned of her job with the dress shop, and

intimated that he might be able to do something for her.

Soon

he had contacted her mother, With the result that Martha, now a good-looking

young girl, entered Fritsch’s luxurious villa in fashionable Moedling as his

ward.

The

merchant, who had been divorced since 1900, became so taken with her that he

also opened his doors and his purse to her half-sister, Paula. Both girls

received the best education — at least in a bookish, institutional sense — that

his money could buy.

Meanwhile,

his own grownup son and daughter, not relishing the changed state of affairs in

the home, went to live with their mother.

Hearty,

generous Moritz Fritsch died in August, 1923. Despite the fact that he had

reached the age of 74, there were whispers alter the funeral that his demise

had been materially hastened by doses of poison.

This

suggestion Breached the authorities via anonymous. letters, However, relatives

objected to an exhumation and autopsy, and they also – perhaps primarily –

feared that the reputation of the department store would not fare well in the

scandal which might ensue.

As

required by law, part of the estate went to Fritsch’s widow and children, while

the rest, including costly furnishings, went to Martha. Thus, at 23, she became

a person of substance as well, as marked personal charmer.

Three

months later she married Emil Marek, 20, who was studying engineering at the

Vienna Technical Institute. He quit school after the marriage and grew a beard,

being self conscious about his bride’s three-year seniority. He also launched

various grandiose engineering plans.

One

of his schemes involved the electrification of Burgenland, the nation’s most

backward province. In his financial negotiations he got the government to agree

to put up a large sum of money – provided he raised the same amount.

While

this matter was pending, young Marek on May 25, 1925, got himself insured, for

a very respectable sum, with the Anglo-Danubian Lloyd company in Vienna.

***

BY

THE TERMS of this policy, he would receive $400,000 in the event of permanent

disability, and in the event of his death his widow would receive $100,000. He

made his first premium payment on June 11.

On

the very next day, something dreadful happened to Emil.

The

story, as told by him and Martha:

He

had been working in the garden of his villa in Moedling. He had been chopping a

block of wood with a razor-sharp axe. The tool had slipped and struck his left

leg at the knee. He had screamed for Martha and she had come running with her

sister, Paula. They had summoned a doctor, he had seen that the leg hung by

nothing more than a sinew, and accordingly had amputated it.

The

Anglo-Dariubian Lloyd company heard the news with displeasure. Marek had paid

out only about $145, and now, they seemed to owe him a net gain of $399,855! It

was the fattest accident claim to come up for collection since World War I.

As

might be expected, the company made an investigation, the first move of which

was to examine the severed leg at the Moedling hospital.

According

to evidence later testified to in court, they found marks indicating that the

member had been struck not by one stroke but by three!

The

company charged fraud in the ensuing weeks and months, the severed leg became

one of the most discussed and debated topics in Austria. Could a man

deliberately chop off his own leg? The insurance company insisted that, for

$399,855, he could.

With

the trial month away, a fresh development made startling news in November 1926.

As

was testified to later, the Mareks had summoned to their home Karl Mraz, a

former orderly at the Moedling hospital,

and suggested: that he should swear at the trial that he had heard certain

doctors say that they had “fixed” the leg wound so that it seemed to have been

the result of three strokes.

***

HE

WAS to say, also, that the doctors had, indicated that the insurance company

would, of course, pay them well for their services.

Word

reached the police and the Mareks were arrested on charges of haying conspired

to defraud the company and to corrupt justice.

The

trial began on March 28, 1927, amid a tempest of publicity; as often happens

when the defendants are young and good-looking, public sympathy was on the side

of the Mareks. How could that young fellow do such a thing to himself? How

could his wife have brought herself to assist him?

Expert

opinion differed on whether the leg had been cut intentionally and by several

strokes, or whether one accidental. blow could have inflicted other marks

automatically.

The

defense suggested that the wooden block Marek had been chopping, and which-had

allegedly been found on top of him by Mrs. Marek might have hit the leg and

contributed to its severing.

The

trial ended on April 9 in two verdicts. On the charge of defrauding the

insurance company, they were found not guilty. On the charge of attempting to

corrupt Karl Mraz, the ex-orderly, they were found guilty and sentenced to

serve at least four months in jail.

Because

of the time they had already spent in custody, the terms were considered

served. Well-wishers flocked about the beaming couple as they left the

courtroom. Policemen had to make an aisle for them as they made their way to a

taxicab at the curb.

Mraz,

meanwhile, had received a sentence of six weeks for having listened to them.

His well-wishers were limited to relatives and friends.

In

the weeks that followed, Martha picked up some pocket money by appearing in

cabarets and in a Johann Strauss operetta. But the Mareks’ really big profit

came when the insurance company settled for about $50,000. However, the Mareks

had to pay more than half the award to defense lawyers and experts.

***

SOON

they were down to $6,000, and that went fast in fruitless financial ventures.

First Marek invested in a taxi fleet, and lost money; then he went to Algiers

and concerned himself with plans to build utilities in North Africa; then, back

in Vienna in 1930, the pair operated a vegetable market, which also failed.

That left them just about broke.

The

family had meanwhile been augmented by the birth of a son, Alfons, in 1929, and

a daughter, Ingeborg, in 1932. Soon after the arrival of the second child, they

moved to a colony of low-cost houses, and Marek ate with his parents in order

to save money. The food seemed to have been altogether nourishing, for he was

in excellent health in July, when he again resumed taking his meals with his

strong-willed wife.

Then,

all of a sudden he became ill. He lost weight and his eyesight failed. Finally

he was removed to a hospital, and he died there on July 31, presumably of

tuberculosis:

Several

weeks later, seven-month-old Ingeborg Marek took sick, and expired on Sept. 2.

The son, Alfons, also became ill but was saved by emergency measures.

The next phase of the Martha Marek record developed in the

spring of 1934, when she began to toady up to a long-neglected great-aunt,

67-year-old Suzanne Lowenstein, widow of an army surgeon.

Mrs.

Lowenstein was so flattered by Martha’s newly-developed interest that; on July

6, that same year, she wrote a new will in which she made the grand-niece her

sole heir.

It

was still June when Aunt Suzanne, fell ill.

Her

sight failed her hair fell put, she lost the use of her, legs. On July 17 she

died.

Martha,

fairly well-fixed again, rented the place on the Kuppelwiesergasse. However,

she liked to spend money, so the inheritance deflated fast, and her landlord

had to attach some of the valuable furnishings willed her by Aunt Suzanne.

***

LATE

in 1933 she cultivated the acquaintance of

Jeno Neumann 49-year-old insurance agent who became first her sub-tenant

and then her suitor. As with Marek, she easily dominated. Neumann and could

readily persuade him that any scheme of hers couldn’t help but succeed.

A few

months after Neumann raved, into his dual role, Martha advertised that she had

a room for rent suitable for a middle-aged lady. She interviewed those who

answered the ad and selected Felicitas Kittenberger, 53-year-old seamstress.

She

assured the grateful Mrs. Kittenberger that, thanks to her wealthy connections,

she

would land her lots of dressmaking customers.

Presently

Neumann wrote an insurance policy for the seamstress in the amount of $950. The

policy was to paid upon maturing to “bearer,” same being Mrs. Marek.

The

usual sequence of swift events followed. Mrs. Kittenberger became ill her eyes

and legs failed, her hair fell out. By June 2 she was dead; and four days later

Mrs. Marek presented the policy. After deduction of taxes, she received $785.

Mrs.

Kittenberger’s son, Herbert, called on Mrs. Marek and angrily accused her of

being a murderess. She had him arrested but the police decided that he let his

temper get the better of him, and sent him on his way.

Which

brings the bulging Marek dossier to October, 1936, and the alleged theft of

valuable tapestries, paintings and jewelry insured to the amount of $2,200. And

to the secret investigation

Inspector

Petemell and another detective, Josef Gunacker maintained a careful watch on

the Marek home, and of the always enterprising suspect. In short order they

began to make interesting discoveries.

From the janitor they learned that on the night of the

reported robbery, Mrs. Marek had removed several large bundles wrapped in brown

paper, and that they had been taken away by a small truck. The janitor had not

noticed anything wrong physically with the woman.

The

officers contacted a cleaning woman who washed Mrs. Marek’s windows and

woodwork each week. Peternell offered her the job of cleaning his apartment at

double the rate she had been getting, provided she went to his place on the day

she customarily worked for Mrs. Marek. He told her to call the suspect, say

that she was indisposed, and would send a substitute.

Thus

it was arranged that on the next regular cleaning day a policewoman reported at

the Marek apartment and tackled the scrubbing job. She could see immediately

that Mrs. Marek enjoyed the best of health.

Before

this, Peternell and Gunacker had located a storage warehouse in which Mrs.

Marek had placed a number of bundles on the evening of Oct. 31, having insisted

that the truck must come for the stuff after dark. The warehouse invoice showed

that the delivered articles were the same she had reported stolen.

***

NOW

the investigation of the fraudulent robbery became an altogether secondary

matter, for the bodies of Emil Marek, Ingeborff Marek, Mrs. Lowenstein and Mrs.

Kittenberger were exhumed and large quantities of a chemical, often used as a

rat poison, were found in each. On top of that, it was established that Mrs.

Marek had been a frequent purchaser, of this poison.

Her

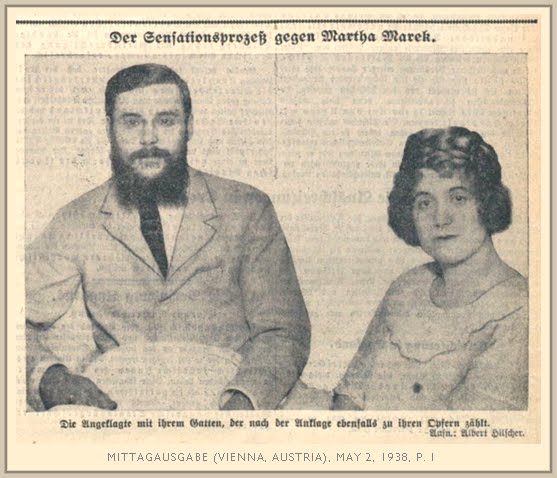

trial for murder, opened on May 2, 1938.

As

large crowds were expected to attend, the ministry of justice had ordered, that

the proceedings take place in the large hall of the courthouse.

The

spectators were not m the least bored by what they saw and heard in the

courtroom, for the “Devil in Petticoats,”‘ as Martha had been dubbed, proved a

spectacular defendant.

Several

times State’s Attorney Wotawa tried to persuade her to confess, indicating that

she might be able to arrange a lighter sentence than death by beheading. But

she shouted back that she would do no such thing, and she stared at him so

fixedly that he said to her, “Don’t try to hypnotize me, madam!”

Another

time he said, “You as a mother maltreated your children,” and she retorted, “I

wish you would be as good a father as I am a mother!”

Another

time she yelled at him, “What do you know about insurance?”‘

Again,

while she was being questioned by the judge about a certain theft, she sneered,

“You know more about stealing than I do.”

Reminded

that Mrs. Kittenberger had become ill after eating at the Marek home, she

replied, “Other people also became sick after meals.”

But

the evidence against her could not be overcome by fireworks or denials. The

bill of charges covered 1,400 pages, and there were more than 100 witnesses for

the prosecution.

One

of them, a druggist, testified that she had bought so much rat poison from him

that he’d had to increase his order from the wholesaler. She had bought many

tubes of the stuff, and each tube, he said, was enough to exterminate 70 rats.

Several

witnesses testified that they had heard her say, before Emil died, that she was

tired of being married to a cripple.

Eugenie

Hellinger, a neighbor, quoted young Alfons Marek as saying, “I shall soon go to

Heaven. My mother told me so.”

***

THE

defendant’s explanation for why Mrs. Kittenberger had named her as the

insurance beneficiary was that she (Mrs. Marek) had loaned the seamstress

$1,100 with which to open a dress shop, and the policy had been security.

But

it was proved that Mrs. Marek at the time did not have $1,100, or

anything near that sum. Nor had Mrs. Kittenberger ever mentioned the dress shop

project to anyone.

Herbert

Kittenberger testified that he saw his mother five, days before she died and

wanted to call in a doctor, but Mrs. Marek had summoned her own physician, who

diagnosed cancer.

Then

Kittenberger wanted her taken to a hospital, but he asserted that Mrs. Marek

had prevented this until the patient had reached what proved to he her last

hours.

Wotawa,

summing up for. the state on May 19, described the defendant as “a cobra in

whom the devil lies.” He said that the “unjust acquittal” in the leg-cutting

case had been “the death warrant for the four poison victims.”

The

five journeymen and four professional judges went through the motions of

deliberating, then returned a verdict of guilty.

Martha

Marek was beheaded on Dec. 6, 1938, the first woman executed in Vienna in 60

years.

[Peter

Levins. “The Case of the Devil in Petticoats,” American Weekly (San Antonio

Light, Tx.), Apr. 25, 1948, p. 28]

[3906-12/31/20]

***

No comments:

Post a Comment