FULL TEXT (of 1928 article):

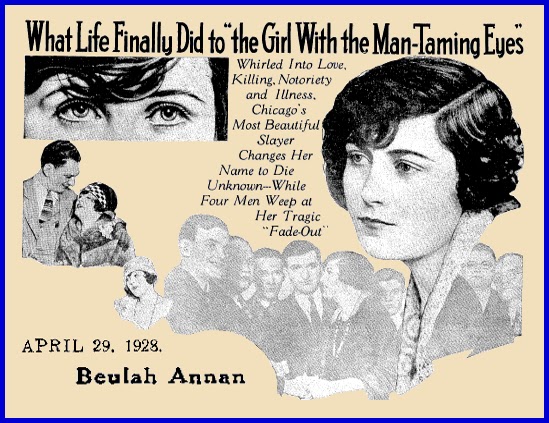

“Her

name was Hula Lou, The kind of girl who never could be true.”

ON

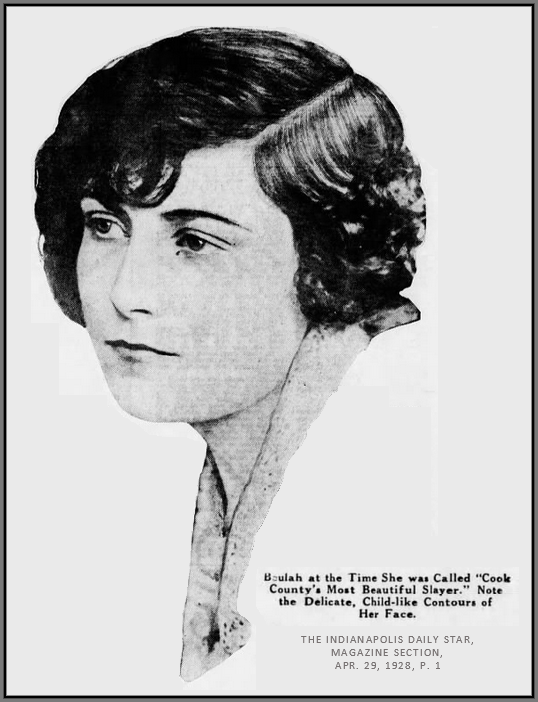

the afternoon of April 3, 1924, Beulah Annan played that, cheap, silly song

madly on the phonograph in her Chicago apartment. Stretched out on a nearby bed

lay her lover, shot to death. Next morning Beulah was famous as “Cook County’s

most beautiful slayer.” She confessed, was tried and acquitted; she went on to

new men and new thrills. And then –

Four

years later, almost to the day, they carried this girl with the gazelle eyes and

wistful mouth back to her tiny Kentucky home in a casket. They played music of

a different sort in the Green River Valley Presbyterian Church – the funeral

march. And four men who had loved her wept, softly and bitterly. Four amazingly

crowded, passion-swept years, then the quick, silent fade-out.

And

some people say philosophically:

“Well,

Beulah Annan certainly lived while she lasted!” But others demur: “What a

frightful waste of youth, beauty, health! What an uncontrolled, purposeless

career!”

Curiously,

both these viewpoints have their justifications.

Beulah

Sheriff-Stephens-Annan-Harlbit was whirled along into love, crime, fame and

death by torrential forces within her and without, which she could not control.

Let us analyze her story and find out why.

Picture

Beulah Sheriff at the age of fifteen, a slim, dark-haired, dreamy-eyed girl,

with strapped books slung over her shoulders, on the way to high school. This

was in Owensboro, Kentucky, a placid village in the Cumberland Valley. She was

a lovely child, and even then they said that everywhere Beulah went the

masculine glances were sure to follow. During that year Beulah married a

linotype operator named Perry Stephens.

A

year later she had a baby, and got a divorce. Later, when she raved and wept in

a Chicago cell, charged with murder, she attributed the start of her trouble to

that first marriage. She intimated that her parents were responsible for her

rushing into marriage before she “knew her own mind.”

But

the schoolgirl divorcee didn’t stay single long. Her second husband was Albert

Annan, a young garage mechanic. They were married in Louisville and went to

Chicago in 1918. Annan was a good mechanic and earned sixty dollars a week; they lived in a small,

furnished apartment, just as thousands of other young married people do in

every large city in America. Al Annan adored his Beulah and she seemed

perfectly happy.

But

she wasn’t. the vivacity and restlessness that helped to make her so attractive

to men made her unwilling to be a stay-at-home, humdrum wife. She had studied

book-keeping and she suggested that she find a job.

This

would mean more money to put in the bank and more pretty clothes for Beulah. Al

agreed, as he agreed to almost everything his wife said. If he could have

looked ahead to the fearful consequences he might have asserted himself and

said no.

Yet you can’t blame Al Annan for those consequences. Thousands of married women go out to work and continue to live well-balanced, happy lives.

Yet you can’t blame Al Annan for those consequences. Thousands of married women

go out to work and continue to live well-balanced, happy lives. Beulah became a

book-keeper at Tennant’s Model Laundry. There were a number of men employed

there; they all admired her and liked to murmur complimentary words as they

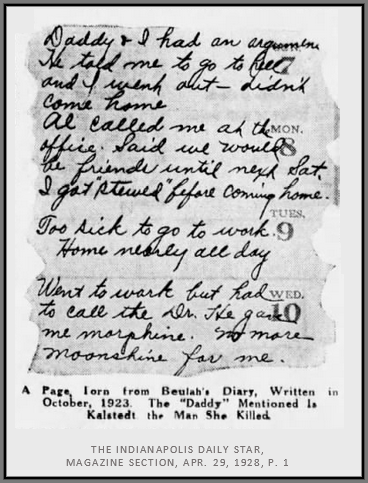

passed her desk. Among them was Harry Kalstedt.

Kalstedt

was the best-looking, youth in the office; he “had a way” with women, just as

Beulah had a way with men. The two personalities came together like a prairie

fire and a haystack. While Al Annan, the faithful, plodding husband, went his

way, believing in his wife, Beulah and Kalstedt were drinking and dancing

together. Then Beulah began entertaining her sweetheart at the apartment during

her husband’s absence. This went on until the day when the girl noticed that

Kalstedt’s ardor was cooling.

By

this time the relations of the two had changed subtly. Beulah was the aggressor, Beulah generally paid for

the liquor they drank. On the afternoon of the tragedy she said she had given

Kalstedt money with which to buy some gin.

He

returned to the apartment with it, they drank, and Beulah put that record on

the phonograph – “Hula Lou.” They embraced, but all the time the fear of losing

the man was gnawing at the girl’s heart and pride. In such a mood quarrels

occur easily.

“I

reminded him,” said Beulah afterward, “of the trust I had put in him, but he

only laughed.”

Finally

she flared up desperately: “Why, you’re nothing but a four-flusher and a

jail-bird.”

This reference to a prison term that Kalstedt had served for trouble with another girl, went home stabbingly. He paled and angrily turned to leave the apartment. In the next room was Al Annan’s revolver. Perhaps Kalstedt turned back, perhaps he saw Beulah running toward the gun. At any rate, those two reached it at about the same time. There was a struggle, a loud report. Kalstedt lay dead on the floor, Beulah was weeping beside him, kissing his face. No one heard the shot. A few moments later Beulah had started the “Hula Lou” record again, and was dancing madly about the apartment.

Two

hours later she telephoned her husband and asked him to hurry home. Then a

strange thing happened. When Al Annan called the police he insisted that he

found Kalstedt in the room and that he had killed him. He held to this story in

spite of a grilling, but there were too many discrepancies.

His

hysterical wife broke down and made three confessions, all of which were later

introduced into the evidence against her.

After

the wronged husband was released he did another generous thing. He drew all his

savings from the bank and hired the best lawyer he could find to defend Beulah.

He stood by her like a rock throughout the most sensational murder trial in

Chicago’s history.

Meanwhile,

a new factor had entered the case. Beulah Annan, who had been just a pretty

unknown wife, became a national and notorious celebrity. Thousands of people in

hundreds of cities read her story, gazed at photographs of her lovely, wistful

face, waited eagerly for her trial. Beulah in her cell felt the stir of all

this; every day she received an armful of “fan mail” from people she didn’t

know.

She

had been frightened at first, but now she began to think of herself as a

heroine. Her lawyers assured her that no woman had ever been hanged for murder

in Cook County, that of forty-eight women who had been tried on that charge

thirty-seven had been freed.

The

trial opened, the day came when Beulah took the stand. She wore a new dress of

navy blue twill, a simple dress designed to emphasize her look of innocence and

childish appeal. Klieg lamps threw a ghastly white light on her face, movie

cameras began grinding. Her lawyer addressed her, oh, so gently:

“Did

you shoot this man?”

“I

did.”

“Why?”

“Because he was going to shoot me.”

That was

Beulah’s defence and it “stood up” with the jury. After two hours of

consultation they returned a verdict of not guilty.

Ovation,

tears of joy from Beulah, much thanking of the jurors. Much snapping of

newspaper cameras as Beulah stood up with the jurors, her attorney, and her

loyal husband.

Next

day she had still another story for her friends, the newspaper boys and girls.

She sat, legs crossed, in the city room of a Chicago daily and murmured softly:

“I

have left my husband. He is too slow.”

“Can you tie that!” exclaimed the journalists,

dashing for their typewriters. But one among their number had a better idea.

She was Maurine Watkins, a girl reporter, who had sat through the trial. She

went home and made Beulah’s story into a play, which was a biting indictment of

the human ego.

Maurine’s

play, “Chicago,” made her famous. If you saw it you must realize that she

retold Beulah Annan’s story almost exactly as it happened. But there was one

phase of the tale the playwright couldn’t tell—the aftermath.

After

Beulah divorced Al Annan he dropped from the picture. He said nothing against

his wife; perhaps he found some satisfaction in the maxims of the moralists

about honesty, loyalty and so on, being their own rewards.

But

Beulah of the spotlight wanted to remain there, and did, intermittently, She

received her divorce decree in 1926 and in 1927 she married Edward Harlbit, a

former pugilist and garage owner. This union lasted only three months, when she

again sued for divorce, charging cruelty.

The

next Chicagoan on whom Beulah turned her “man-taming eyes” was A. Marcus. She

was engaged to marry him when she became ill. Her hectic life in the mid-west

metropolis was demanding its toll.

Suddenly

it seemed as if Beulah had come to her senses – too late. The lights, the

clamor, the clicking cameras, the craving for publicity faded away and became

hateful to her. She became “Dorothy Stephens” – taking her first husband’s name

– and entered the Chicago Fresh Air Sanitarium.

At

last she was unknown again, just a pretty, pale-faced girl,. far gone with

tuberculosis, sitting, day after day, bundled up in a wheel chair on an open

porch.

After

her death at the age of thirty-two, Marcus took her body back to Owensboro,

Kentucky. When the burial services were over he put a wreath over her grave, wept, and went away.

[“What Life Did to ‘the Girl With the Man-Taming Eyes,” Salt

Lake Tribune (Ut.), Magazine sec., April 29, 1928, p. 3]

***

***

***

***

***

***

[2396-3/3/22]

***

No comments:

Post a Comment