EXCERPT from Italian Wikipedia:

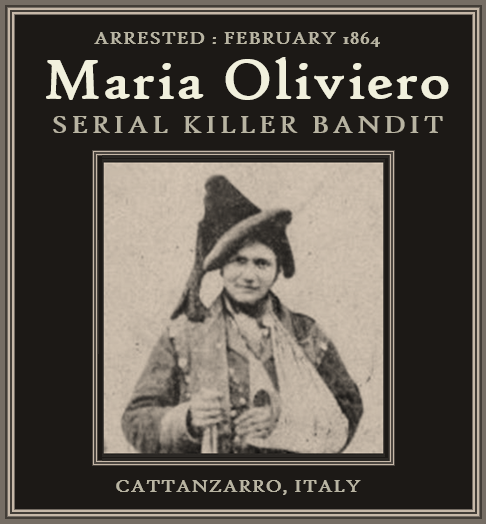

At the age of twenty, Maria Oliviero murdered her sister, hacking her 48 times with an axe for slander and joined the gang of her husband, Pietro Monaco. She was arrested in 1864 and went on trial in February, was charged with 32 crimes: kidnapping, violent robberies and thefts, fires, and murders. She confessed to the murder of his sister, but for the rest she claimed she was coerced into participating.

***

FULL

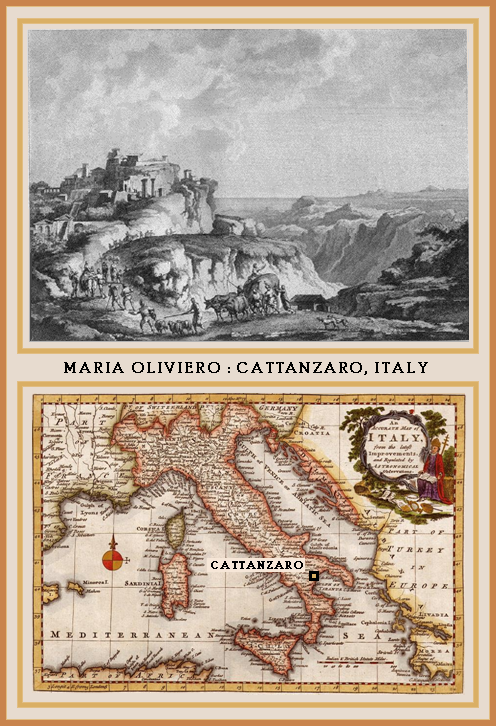

TEXT (Article 1 of 2): A Turin letter states that among the Neapolitan provinces which

have to contend with the dreadful scourge of brigandage there is that of

Cattanzaro, which possesses the advantage of having a band which is led

by Maria Oliviero, an exceedingly handsome woman, not yet thirty years

of age. Barbarity is her chief characteristic, and the sight of blood

renders her as excited as a wild beast. She was the wife of a famous

brigand, Moneco, of the Albanian village of Spezzano, who was killed in

an encounter with the Italian troops near Rossano. In this very

encounter Maria was also wounded, but she continued to discharge her

musket, kneeling on the dead body of her husband, with a firmness and a

courage which even commanded the admiration of her opponents. Having at

last been struck in the right leg, she fell into the hands of the

troops, was brought before a court-martial at Cattanzaro, and condemned

to be shot.

The

sentence was, however, commuted to thirty years penal servitude. While

she was expiating her crimes in the prison at Cattanzaro the gaoler fell

desperately in love with her. The cunning woman pretended to feel an

equal affection for him, and one day she told him that while she was

with her husband she had concealed in at place near Rossano a large sum

of money, which had been paid for the ransom of a rich farmer. The

gaoler went quickly to the spot and found the money.

This

fact had naturally the effect of making his love for Maria still more

ardent, so that she had no difficulty in convincing him that tender

affections are better manifested in freedom than within the four walls

of a dungeon. Before, however, making their escape Maria succeeded in

sending word to her brothers, who are brigands, that on a certain

evening she would be at an appointed spot, not far from Cattanzaro,

attired in man’s clothes, together with her deliverer. Maria was

punctual at the rendezvous, and her brothers also. The unfaithful

turnkey was killed out of hand, and the money he had found replaced in

Maria’s pocket. Once free, this woman organised a band of brigands, and

began her operations in that tract of mountains which lie between the

river Crati and Cattanzaro.

The

barbarities since perpetrated by Maria are almost incredible. The

villages of Spinelli, Cotzenei, and Belvedere have been literally sacked

by the band she commands. The dread which the name of Maria Oliviero

inspires among the rural population of Cattanzaro is so great that the

Italian government have been obliged to send two battalions of the line

to pursue the cruel fury.

While

the band led by this woman is desolating the country of Cattanzaro, we

hear from Rionre that Bersaglieri have succeeded at last in capturing

the famous brigand, Sacchitiello, together with the two still more

famous mistresses of the brigands Crocco and Schiavone.

The strangest thing about the capture of Sacchitiello, and the two women, is that they were taken in the house of the captain of the National Guard of the village, where they had been concealed since the month of July. This fact shows how difficult it is to get rid of the Neapolitan brigands, since, in certain cases, the commanders of the National Guard give them safe shelter in their very houses.

The strangest thing about the capture of Sacchitiello, and the two women, is that they were taken in the house of the captain of the National Guard of the village, where they had been concealed since the month of July. This fact shows how difficult it is to get rid of the Neapolitan brigands, since, in certain cases, the commanders of the National Guard give them safe shelter in their very houses.

[“A Female Brigand – Her Atrocities,” Camden Democrat (N.J.), Mar. 4, 1865, p. 1]

***

For similar cases, see: Female Serial Killer Bandits

FULL TEXT (Article 2 of 2): From the Liverpool Post. – We recently published

some intelligence respecting brigandage in Italy which discloses one of the

most abnormal of the phenomena connected with that barbarous anachronism. The

system which is now going on in the name of religion and Divine right is not

like ordinary brigandage. It seems a relic of some ancient state of society

which has long since passed away. If those monstrous and carnivorous animal

forms which we have seen in stucco at Sydenham were to reappear, again in the

flesh, they could hardly be more out of date. It is not merely that the loyal

and devout brigands, in their zeal for the service of the Church and the

Ex-King of Naples, do not content themselves with vulgar robbery and murder,

and delight in mutilation and burning alive, but that women are actually found

to join in these things, and to emulate the men in cruelty and ferocity. This

extraordinary combination of devotion and loyalty with brigandage and

cannibalism, is a marvellous phenomena, and warns us what fanaticism may become

when divorced from morality. No doubt the appetite for plunder may be at the

bottom, but there is also very sincere faith that at least one of the ends

sought to be attained sanctions the nefarious means employed to promote it.

The band of NICOLI MASINI has for four years been the terror

of the Basilicata. During all this time it has been incessantly engaged in

robbing and murdering, mutilating and burning alive the unfortunate wretches

who happened to fall into its hands. It consists of about seventeen persons,

but three of them are women, who are described as being more blood-thirty and

pitiless than the men. Whatever the inferiority of woman may be to man in

physical strength and power of mind generally, in this case it would appear

that the brigandesses have vindicated for themselves not merely a bad equality,

but a bad preeminence. One of the most curious circumstances of the case, too,

is that these ladies appear to have been originally carried off by force. Their

connection with the brigands appears in its origin to have been a kind of

Sabine rape, only upon a very reduced scale.

Another difference seems to consist in this band of brigands

not having been able to procure or to maintain a wife apiece for each man, as

the Romans are said to have done. It had to be content with three wives, the

rest of the gang, of course, remaining bachelors. Whether it is one of the

exaggerations of romance with which each incidents are pretty pure to be

decorated, or whether it is simple matter of fact, we do not know; but,

according to the statement before us, these three brigandesses are young and

beautiful. What, however, lends a color of probability to this is, that it is

not likely the bandits would have been at the trouble of carrying off brides

who were elderly and plain. The whole gang is now, luckily, in custody, and

will soon be brought to trial. As the counsel for the ladies are not, we

suppose, in a position to produce the marriage certificates of their fair

clients, and as the Italian law might not hold those scraps of paper to be a

sufficient justification for any crime which a wife might commit, it only she

did it in company with her husband, it is presumed that these cannibalesses

will not be allowed to escape with impunity. There are said to be no less than

314 distinct charges against them for crimes the they are known to have

committed. What proportion the number of crimes that may not have been brought

home to the band bears to this, is of course impossible to say. The known

number gives an average of rather more than eighteen crimes a head for the

brigands and brigandesses uniformly. Among these charges, besides more robbery,

the crimes of mutilation, murder and burning alive are said to figure

conspicuously. To extend an ill-judged lenity [sic] to such persons, is practically

to offer a direct premium for the perpetration of the crimes to which they have

devoted their lives.

This phenomenon of female brigandage is not, however, by

any means peculiar to the band of NICOLA [Nicoli?] MASINI. We have seen that

these brigandesses have an average of eighteen crimes against them in common

with the men. But they have not yet risen to a level with one of their fair

predecessors, a certain MARIA OLIVIERI, of Calabria. This incomparable heroine,

when she was arrested about a year ago, had no less than forty distinct capital

charges against her. Forty murders she was known to have committed, and one of

her victims was her own sister. She also was described as young and beautiful;

and if in these qualities she did not surpass the three amazons of MASINI's

band, she must be at least allowed to hold a far higher rank as a homicide. The

most authentic account given of her states that she was a very fine-looking

young woman indeed, and was certainly not more than twenty-three years of age.

Forty murders would, therefore, be at the average rate of almost a couple for

every year of her short life. Whether the brigandesses as well as the brigands

are primarily actuated by the desire of plunder, but seek to turn their

favorite avocation to account in the service of their church and their king,

must furnish the element of an interesting problem. Those who patronise and

encourage such worthies, of course take care to impress upon their credulous,

superstitious minds that by serving the cause of Divine right, and fighting the

good fight of the soldiers of the faith, at the same time that they are filling

their pockets with the money found in farm-houses and upon travelers on the

highway, they will be laying up for themselves treasures in heaven. And of

course the ignorant brigands firmly believe what their priests tell them. In

the eyes of fanatics of this sort morality, and religion have nothing whatever

to do with each other. So long as they do the bidding of their spiritual

guides, repeat by rote the set number of prayers, abstain from eating meat on

fast-days, and go through the other prescribed formalities, they are in no fear

about their soul's health. The Italian brigand, and therefore, we suppose, this

new development, the Italian brigandess also, is traditionally a very pious

animal, as he understands the meaning of piety. Having fulfilled the higher

obligations of his law, he feels he may safely dispense with such insignificant

duties as honesty and morality. What, indeed, would be the use, he seems to

argue with himself, though perhaps half unconsciously, of so strict an

adherence to his religious rites if it did not purchase a corresponding

immunity from the inconvenient restraints of more secular virtue? This would

apply in the case of mere vulgar brigandage in ordinary times, when there was

no forlorn and fugitive King, no persecuted faith to champion. But now the

brigand not merely enjoys the privilege of a moral carte blanche, in

consideration of a strict observance of pious forms, but he is enjoined to use

his carbine and his dagger in the service of his church and his king; and, what

is more, he serves himself profitably in serving them. Of old time, the

traditional brigand was generally depicted with his wife to cheer the solitude

of his retreat. But she was a domestic household personage of the ordinary

type. She might, indeed – if his cave in the rocks, or his hole burrowed in

the side of a hill, were scented out by the minions of justice – seize a

carbine or a dagger and fight for her life; but murder and robbery were no part

of her ordinary duty. That department was left to the brigand. The sphere of activity

in which the brigandess occupied herself was the preparation of the meals, the

sorting and storing away of the booty, and the like. But this is an age of

progress with development in all things, and the brigandess is asserting her

equality with her lord and master the brigand. Still, there must be some new

principle at work to account for this singular phenomenon. That women might

like to vote at elections, and even to represent their fellow-citizenesses in

Parliament, or to dress like bloomers, one can understand. But why should

woman, naturally more timid than man, brave all the perils of brigandage when

she might stay quietly at home and leave such dangerous work to her husband? It

is because women, being more susceptible to superstitious influences than men,

have, for obvious reasons, been worked upon for sinister and evil purpose by

those who are interested in promoting brigandage in Italy.

[“Brigandage In Italy.; Beautiful But Cruel Female Robbers.”

(From the Liverpool Post) New York Times (N.Y.), May 28, 1865, p. 2]

***

***

Aug. 30, 1841 – born, Maria

Oliverio, known as Ciccilla,

Casole Bruzio.

Oct. 3, 1858 – age of 17, married Pietro Monaco,,

moves to hamlet of Macchia in the municipality of Spezzano Piccolo.

Mar.17, 1861 – King Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia is proclaimed King of

Italy.

Mar. 1862 – arrested, along with her sister Teresa by

Major Pietro Fumel.

1862 – murders sister Teresa for slander, with 48

strokes of an ax and in the presence of Theresa’s three children.

May 1862 – joins Pietro Monaco’s band of brigands. Calabria; loyal

to king of Naples.

June 18, 1863 – Band seizes cousins Achille

Mazzei and Antonio Parisio in Santo Stefano (current Santo Stefano di

Rogliano); ransomed of 20 000 ducats.

Aug. 31, 1863 – Band seizes of 9 people, including nobles, religious

and owners of Acri.

Sep. 1, 1863 – General Giuseppe Sirtori assumes

command of operations against brigandage in Calabria Citra and Ultra.

Dec. 23, 1863 – monk killed by members of Monaco’s

Band.

Feb.15(?) 1864 – capture of Maria and Monaco’s Band.

Feb. 1864 – Charged in Catanzaro by the Calabria War

Tribunal, Ultra,Maria was sentenced to death.

Feb. 1864 – sentence commuted to life of hard labor.

1879

(circa) – Maria dies, presumably (but not certainly) at Fenestrelle

Fort, Turin.

[Source, Italian Wikipedia]

***

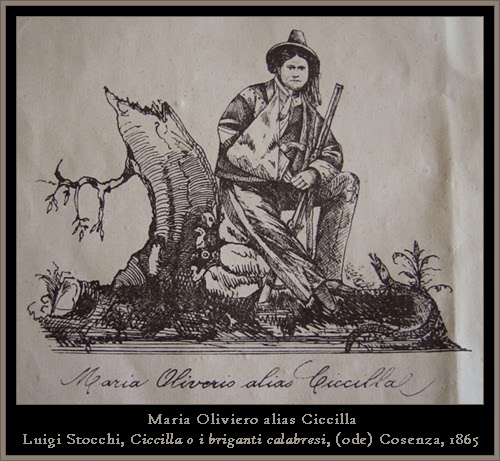

Beheading of Pietro Monaco – In an effort to repress

banditry, government agents would cut off the heads the brigands they killed

and put them on display, as a warning to the population. According to a poet

and journalist of the time, Luigi Stocchi, Maria tried to pursue the

killers, then returned from the corpse of her husband and beheaded him to

prevent the Piedmontese soldiers were doing it. She burned his head in a big

chestnut tree (still extant), near the place of the ambush and fled to Sila with her brother Raffaele, to her husband’s cousin

Antonio and to the rest of the gang who took refuge in the nearby caves.

Alexandre Dumas, offers a different version of events "One of the owners of

Cosenza who had been right to cruelly hurt his head ... he cut off the head of

Monaco, dried it in an oven and kept it indoors to adorn his desk"

[Italian Wikipedia]

***

For similar cases, see: Female Serial Killer Bandits

[3076-1/10/21]

***

https://www.ibs.it/ciccilla-storia-della-brigantessa-maria-libro-peppino-curcio-alexandre-dumas/e/9788881016938

ReplyDelete