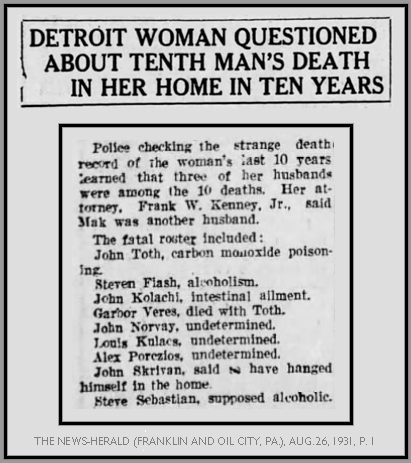

[“Witness Says Lodger Pushed From Window,” syndicated (AP), Bluefield Daily Telegraph (W. Va.), Sep. 3, 1931, p. 1]

FULL

TEXT (Article 7 of 9): The “Old Gray Witch of Medina Street” sits in her tiny room in the

Michigan House of Correction at Plymouth. Imprisoned fear life, far from her

native hills of Hungary, she talks to no one. All through the past Winter she

was silent, shunned and feared by her fellow-prisoners. Even now seeing from

her window the trees budding and the grass turning green, just as the Magyar

slopes came to life in the Spring in her native town of Sarud, she keeps a

seemingly mystic vigil, her strange eyes fixed upon objects which do not exist.

Perhaps

it is just as well for her that things beyond her window panes do not intrigue

her, for by the terms of her sentence she will never again be nearer them than,

she is now. Twelve men died, tragically in hear house; three were suicides. And

the other nine? In charging the “witch” with murder, the State decided to

concentrate on the case of Stephen Mak, the twelfth man to die.

It

was last August 21st.

In

the front yard of her home on Medina Street in the Hungarian colony of Detroit,

11-year-old Marie Chevalia was playing. All morning she had been making mud

pies.

It

was a warm day, but the air was heavy, and dull smoke from surrounding

factories resisted the sunlight. Against this background of haze; the house

directly across the street from the yard where little Marie was playing looked

somewhat ghostly.

The

reason, perhaps, lay in the legends of Medina Street.

Almost

from her cradle days, little Marie Chevalia had heard people say strange things

about that house and its inmates.

“Behind

those filmy curtains,” Medina Street mothers told their, .children when family

circles were gathered around the hearths, “stalks a bad witch-woman. Her name

is Mrs. Rose Veres. She bewitches factory men, they go to live in her house,

and in the cellar the witch-woman brews potions. She has the Evil Eye. When she

looks at these men, they have to do when she tells them. They want to go away,

but they can’t. She bewitches them. Then they die.

“She

was born with a full set of teeth and a veil, and if she wants she can change

herself into a wolf or a hare.”

In

the Old World, among the Magyrs, in the Hungarian hills whence most of these

people had come, so-called witches were common. Other people didn’t have to

believe in them if they preferred not to, but all the cynical sophistication in

the world couldn’t take the vampires and other evil spirits out of the darkness

which descended upon Sarud and Nagyrev every night.

These

people knew. They had seen the vampires. They had seen the wolf-men and the

wolf-women and beard their blood-curdling cries whenever anyone in the village

died.

So

Mrs. Veres, it was clear, was a “witch,” even though she lived in Detroit, in

the United States of America.

Why,

many times she had been seen growling about the alleys at might, garbed in her

long flowing garments of black flannel, a cape tucked tightly about her stooped

shoulders and her hair covered by a lace boudoir cap.

On

such occasions it was considered unsafe to be abroad in the darkness. And when

the word would go out that “The Witch of Medina Street” was on a nocturnal

prowl, every door in the neighborhood would be locked and double-barreled, and

every shade drawn.

So

little Marie Chevalia, as she fashioned her mud-pies last August 21st,

was glad that she was in her own yard, glad that it was daylight, glad that she

was in her own yard, glad that her Mamma and Papa had warned her against the

bad witch.

Soon,

as Marie watched, Mrs. Veres stopped out from behind the front door. Marie

dropped her mud pies and stared.

Mrs.

Veres, her net boudoir cap on her head, descended the steps and spoke a few

words in low tones to John Walker, a colored man who had been sprinkling the

lawn. Walker was one of Mrs. Veres’s boarders, and occupied an attic room. At

the “witch’s” direction, he dropped the hose and retired to the cellar to shut

off the water and perform some other duties.

As

soon as Walker had disappeared’ behind the house, little Marie saw Mrs. Veres

pick up a long ladder and place it against the side of the house. Then,

clutching her skirt, beneath which she was accustomed to wear five or six

petticoats, the “Old Gray Witch of Medina Street” walked back into her house

and closed the door behind her.

Transfixed,

by vague fears and a very definite curiosity, Marie remained, wide-eyed,

squatting over her mud pies. Probably because she was a member of the more

curious sex, little Marie’s curiosity was stronger than her fear. That is why

she was later able to recount the entire drama as it unfolded before her young

eyes.

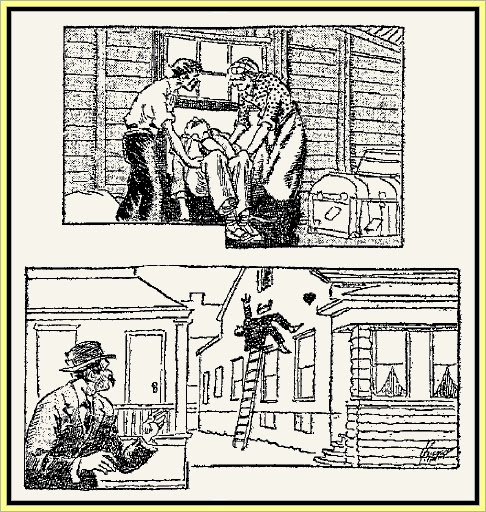

Presently

an old man emerged from the “witch-house.” He was unsteady on his feet. He was

carrying a small box and a hammer. Marie recognized him as Stephen Mak, one of

Mrs. Veres’s boarders. He walked toward the ladder and put a foot on it.

Hesitantly

he climbed, step by step. At the top he paused to lay his hammer and box on the

ledge. Then he opened the window, pulled himself partially through and sat on

the sill. For a full minute he remained in that position – then before the

watchful eyes of little Marie, be suddenly disappeared.

George

Halasz, a short, swarthy man who lived nearby, was strolling along

Medina Street. Up to this point, he had seen nothing unusual. From the sidewalk

he called once or twice for Mike Ludd, a friend who boarded at the Veres house.

Receiving no immediate reply, Halasz leaned against a tree and started rolling

a cigarette.

A

moment later Walker returned from the basement, rear, and began walking toward

the street. He was almost directly below the attic window when a box of nails

dropped in front

of him; then a hammer thudded. He raised his hands above his head and drew

back, then looked up. As he looked, the body of Stephen Mak hurtled through the

attic window head-first, crashed against the side of the house next door and

plunged headlong to the

ground.

Walker

raced to the back door and shouted loudly for Mrs. Veres. George Halasz removed

his newly rolled cigarette from his mouth and looked on in amazement.

Marie

Chevalia screamed and ran into her house.

Marie’s

screams aroused the neighborhood and quickly a crowd gathered around the Veres

home. Its gong clanging, an ambulance swung into Medina Street, and fifty-five

minutes later the ‘Widow Veres” her face noticeably dirty and her head covered

with cobwebs, calmly and inquiringly entered her yard from the alley beyond.

Mak was taken t» the Detroit Receiving Hospital, where he died two days later.

Mak’s

death

went into the preliminary official reports as an accident. Mrs. Veres

told police that she had asked him to fix the window, and that he had

presumably

fallen because of his age and infirm condition. At the time, she

explained, she

had been shopping, and her elder son, William, was at a movie. Walker

corroborated this story. Police were not suspicious. Mrs. Veres’s

reputation as

a “witch” was not taken seriously beyond Medina Street.

But

rumoxs began, to get around. Mak was the twelfth man to die prematurely after a

residence in the Veres house. The first was Veres himself. The. rest were

boarders. And little Marie Chevalia kept telling her mama that “the witch

killed Mr. Mak. I saw her face in the window.” George Halasz was quite sure of

that, too.

Then

it was discovered that the window Mak went up to fix needed no fixing; that he

wore shoes when he went up and none when he came down, that he had told

neighbors he was afraid of Mrs. Veres and was sure that she was going to kill

him; that there were marks on his head which looked like blows; and something

in his stomach which might not be just liquor.

It

was revealed, too, that on the morning of Mak’s death Mrs. Veres had cut a hole

in the attic partition through which a man’s body, might drawn, that

that she had offered Walter $500 to “keep his mouth shut” about his suspicions.

Officials

of insurance companies volunteered the information that Mrs. Veres had a $5,000

policy on Mak’s life, double indemnity in case of accidental death—and that she

was; still trying to make collections on policies issued to her on the lives of

dead former boarders. It was revealed, too, that she owed $1,000 to her

next-door neighbor, Aaron Freed, and had promised to pay him “as soon as I

collect some insurance money.” Police soon found a trunk containing over

seventy-five policies taken out by Mrs. Veres since she moved to Detroit.

William,

her elder son, had testified that he was, at a movie at the time of Mak’s

“fall.” But John Veres, the widow’s younger son, frankly told detectives

another version.

“Bill

told me to say he was at the Grand Theatre,” John told officers. “But he

wasn’t. He was at home with Mother.”

William

Veres was destined to share his mother’s fate. He, too, received a life

sentence, in spite of his youth. Old Mrs. Veres sits motionless in the House of

Correction. ‘Her eyes’ seem fixed upon objects.

[“While

a Little Girl Watched the Old Gray Witch of Medina Street – The Hungarian Widow’s Twelfth Boarder Tumbled to His Death, But Marie of the Mud Pies Saw All, And Told!”

Ogden Standard Examiner (Ut.), Apr. 3, 1932, page number unknown]

***

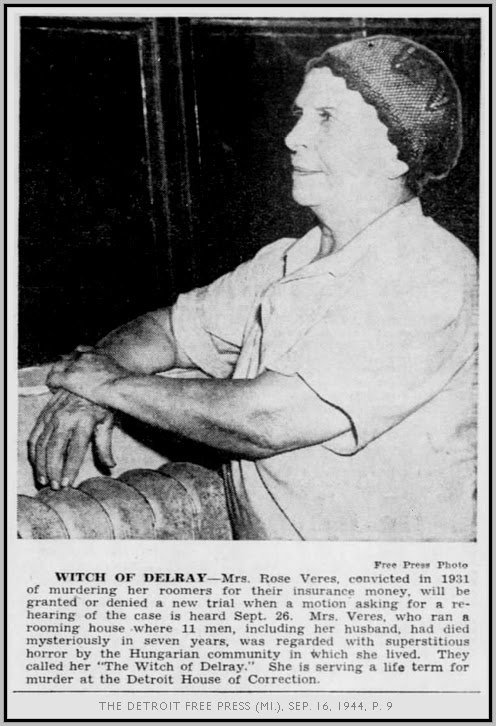

FULL TEXT (Article 7 of 8): At lost

relentless justice has been meted out to America’s most cold-blooded woman

killer – Mrs. Rose Veres, known as the Witch of Delray. She was responsible for

the deaths of 12 lodgers – simple Hungarians whose lives she had insured.

FREEDOM’S door has been slammed on

the Witch of Delray.

The air she breathes for the rest of

her days must be screened through prison bars.

There will be no recapture of the

years when she roamed the streets of Detroit, frightening children and killing

men.

The Witch of Delray, who actually is

Mrs. Rose Veres, murdered for profit, which is why she was sentenced to life

imprisonment in Michigan.

For a time, while lawyers were

fighting desperately for a new trial for her, it looked as though she might be

free again. But now Recorder’s Judge John J. Maher, at Detroit, has denied her

appeal.

Mrs. Veres made a good thing of being

a witch. She got away with it for seven years, during which time she became a

legendary figure in black, and by the time the law caught up with her the

number of her victims was reckoned at 12. Her bank-deposits for the period

totalled £23,000.

DASTARDLY PLAN

She worked out a simple plan for

living by the death of others. She took a rooming house in the Delray section

of Detroit, where most of her lodgers were, like herself, Hungarian born. They

were simple folk and Mrs. Veres volunteered to look after their money. At the

same time she insured their lives.

When police got interested in the

goings-on in her home they discovered 75 insurance policies on her boarders, in

all of which she was the beneficiary. She had a reason why.

“I kept insurance policies on most of

my boarders,” she said, “because that is the way my people do. We want a good

funeral. There must be flowers and lodge members. I gave everyone a fine

funeral.”

The police thought too many fine

funerals were being held at the frame dwelling on Medina-street.

ACCIDENTS FAKED

They became curious when Steven Mak,

68, tumbled from a ladder out side the Veres household and died of a fractured

skull. They began asking questions and soon discovered he was the 12th man to

die at the Medina-street house since September 21, 1924, when Steven Sebastian

suffered what was described on the death certificate as a fatal cerebral

haemorrhage.

After a little inquiring in the

neighborhood, detectives found Marie Chevalia, 11, who was making mudpies

outside her home when Mak fell. “I saw Mr. Mak go up the ladder,” she said.

“Mrs. Veres was holding it for him at the attic window. He was right at the attic

window. He swayed and moaned, as if he was sick.”

Her story spun a web around the Witch

of Delray when she added:

“While he was falling, Mrs. Veres and

William (her son) poked their heads out of the window.”

Yes, that was right, Mrs. Veres remembered. She had asked Mak to repair a window. But the police said the window

didn’t need repairs.

Then there was the story of John

Walker. Mrs. Veres, he said, told him to water the ground where the ladder

rested, and the Witch herself placed it on the slippery clay.

And there was £2000 insurance on

Mak’s life.

A jury believed that Mrs. Veres and

her son pushed Mak to death and returned a verdict that provided the maximum

penalty under Michigan law for both – life imprisonment.

Responsibility for the 11 other deaths

wasn’t proved against Mrs. Veres. But the police discovered many strange

circumstances as they delved into her dusty past.

They learned that her husband, Gabor,

and Laszlo Toth, a boarder, were working on a car in the Veres garage one day

in 1927 when suddenly the door slammed. Both died of carbon monoxide poisoning

generated by the automobile exhaust.

EIGHT MEN DIED

They heard about men whose names were

known as John Nordal, Balit Peterman, Gabor Feges, Steven Faish, Alex Porczio,

Berni Kalo, John Sokivon and John Coccardi. All of them slept on wall-lined

cots in the dirt floored cellar.

All of them had casks of wine between

their beds. All of them died. Some said their deaths were caused by lye in the

wine.

While all these things were happening,

Mrs. Veres was becoming known around the neighborhood as a sinister character.

The Detroit district in which she

lived was mainly populated by native born Hungarians – simple folk who still retained many of the

customs and beliefs of the old country.

To them werewolves, human vampires

and witches were very real beings – beings that could do harm to innocent

people who crossed their path.

BRANDED A WITCH

So it is not surprising that locally

the notorious Mrs. Veres should be looked upon by these people as a witch.

That when she appeared, the pious

people should devoutly cross themselves for fear of the evil eye.

Some said she was born with a full

set of teeth and a veil. And some said:

“If she wants, she can change her

self into a wolf or a hare.”

That’s how she became the Witch of

Delray and why she was feared by both adults and children.

Although prison claims her, her spell

continues.

Almost two years after she was gaoled

John Kampfl, one of her basement lodgers, cut his throat. It was not a critical

wound. Doctors said he would recover.

“No,” he said. “The Witch cast her

evil eye on me.”

The next morning he died, which

probably isn’t the reason the courts refused her a new trial.

But who knows?

Mrs. Rose Veres murdered ruthlessly

for profit while she was becoming known as the Witch of Delray?

The way the jury figured, William

Veres was as guilty as his mother.

[Gerald Duncan, “America’s Female

Bluebeard Is in Gaol For Life,” World’s

News (Sydney, Australia), Jun. 30, 1945, p. 6]

***

FULL TEXT (Article 9 of 9): Detroit, Mich., Dec. 10 – The

“witch of Delray,” central figure 13 years ago in a murder trial which

ended in her conviction and a life

sentence after bizarre testimony linking her to 11 other deaths, was a free

woman tonight by reason of a “not guilty” verdict in a belated retrial.

She is Mrs. Rose Veres, now 64, who for many years kept a

rooming house and kept a rooming house was a two story frame building in what

was formerly the village of Delray. This community, made up for the most part

of Hungarian and middle European immigrants, is now part of Detroit.

~ Son Convicted, Too ~

At the retrial a jury of eight men and four women took eight

hours to vote an acquittal for the widely known “which,” who was convicted

originally with her son, William, of first degree murder for killing Stephen

Mack, a roomer, by pushing him out an attic window.

Mrs. Veres and her son served 13 years of their life

sentences and recently won new trials on a Supreme court ruling that their

convictions were invalid because of the absence from the courtroom of the

presiding judge when the verdict was returned.

~ Courtroom is Packed. ~

When the new trials were ordered, prosecuting authorities

released William Veres to stand trial again. The retrial began Nov. 26 before

Recorder’s Judge Paul E. Krause, and each day’s session has been in a courtroom

packed with present and former Delray neighbors and residents. Mrs. Veres

speaks no English and testified thru an interpreter.

Evidence was produced at both trials that Mrs. Veres’

rooming house had the local reputation of a “house of dreath” because of the

deaths there of 11 other persons other than Mack between 1924 and 1931.

Children feared her, it was said, because of her long hair and reported

“baleful eye,” and the name “witch of Delray” was applied to her.

When Mack died from a fall from Mrs. Veres’ attick window he

had a $4,000 insurance policy, of which Mrs. Veres was the benedficiary. Police

later found 75 insurance policies in the names of roomers.

[“’Baleful Eyed Witch’ Is Free After 13 Years – Wins In New

Trial Over Old Death Case,” Chicago Tribune (Il.), Dec. 11, 1945, p. 5]

***

EXCERPT: It had been the custom each time one of her roomers

died to have photographs made of the funeral showing her giving the corpse a

final embrace. [Curtis Haseltine, “Murder for Money – Case of Delray’s ‘Witch’

Up Again,” The Detroit Free Press, Aug. 27, 1944, Magazine Section, p. 7]